He that plays the king

He that plays the king |

|

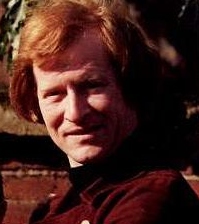

Alan Howard is in his prime. Tall, slender, strong with floppy hair and short-sighted blue [sic] eyes, he is attractive to women, commanding when necessary but frequently overlooked in a crowd. Autograph-hunters at the stage door, waiting for a monarch, have failed to stop the shambling figure in glasses, jeans and duffle coat. He is hard to imitate and seems able to play with a minimum of make-up any physical type- 'From Seven-Stone Weakling to Incredible Hulk', as one headline had it - by turns Richard II, all poetry and sweetness, and Richard III, full of prose and horror: the one a true king who becomes a man while losing a throne, the other a usurper who becomes a monster while grabbing one.

A natural reaction to glancing over Howard's glittering and versatile achievement is to wonder why he is not more famous. He has been with the Royal Shakespeare Company for 14 years, almost without interruption, and when he started he played important roles immediately. Why isn't he more of a star? The answer is that he is a star, both to audiences abroad (he has led many foreign tours) and to the small but enthusiastic section of the theatrical public that goes to Stratford or the Aldwych.

Forced to speak of himself rather than Shakespeare, he is extraordinarily hesitant, so that you long to rush into the lengthening pauses and reassure him that it really does not matter all that much about that question and, if it has turned out to be so agonising, why not try this one? But even talking about something already accomplished, safely recorded, he can find no relief from the evident pain of formulation. The first television serial in which he stars, Cover, begins its run of six episodes on Thames Television on January 20, and is likely to bring about some rectification of the imbalance between his accomplishment and the wider public's recognition of it. When I asked him what it was about, he replied with every appearance of tortured despair: ". . . Um . . . it's er . . . it's quite difficult to describe. It's a thing written by Philip Mackie. The theme is sort of deception. I think... Yes it is [brightening], it's deception. It seems to be that's sort of one of his... interests." That took almost two minutes, with the words coming in little hurried clumps.

This manner has made him appear a solemn student, full of virtues like industry, intelligence, and seriousness - and a bit dull. His domestic life, with journalist Sally Beauman and their only child James, is solid, happy and central to his existence. His relaxations are the exemplary ones of literature and music (and 18th century music at that, nothing vulgar from the 19th).

One of his closest friends, Norman Rodway, joins with Sally Beauman in denying this sober image. But they can only dent rather than destroy it. Rodway and Howard shared a house at Stratford in the late 1960s. After performances they would wind down with a few drinks. 'He has a marvellous frivolous side that you don't really see until three o'clock. Or he can get into terrible rages. That tends to happen towards four o'clock. It only makes me laugh. It's not a sudden explosion; it's a slow seethe that finally comes to the boil. He would adopt ludicrously extreme opinions: that the only art form in the world was the theatre, that everything else was rubbish, music was rubbish, poetry was rubbish. I just used to say 'Time to go to bed now, Alan...' One time we had been up practically all night, we had a call for The Revenger's Tragedy at 10 0'clock and the stage manager came and gave us a knock at my door at about five past. So I dashed out of my bed and into my clothes and ran downstairs shouting: 'Come on' we're late!' And this nude figure appeared on the landing with a syringe saying, 'I am sorry I must have this shot before we go'. I thought: 'Good Heavens, I'm living with a junkie.' I had known him two years and I had no idea he was a diabetic." Few people have; he does not let it influence his behaviour.

The temper is elaborated by Sally Beauman. "He is volatile, very up and down from day to day and moody. And he has a very loud voice. When he's really angry, the decibels - well, it's intimidating. Then he'll play music so loud that the whole tone is distorted. So it echoes up the house and along the street. It's impossible to talk through it."

But for the most part he is controlled and it is in an even voice that he censors himself so that no imprecision shall escape. Terry Hands, who has directed all eight of the histories and developed a rapport with Howard which approaches telepathy, describes his working method as: "Amorphous. Like painting. He doesn't work through detail. He covers whole areas in green and blue and then explores other bits and then at the very last moment puts in the shadows and highlights."

In order to block in those patches and decide on their shade, Howard takes the examination of a text to extremes. Naturally it is most noticed when this attention is lavished on apparently insignificant phrases. This teasing leads to, and is part of, the new quality that Howard has brought to playing Shakespeare.

Hands explains: "His technique is brilliant, but it is linked to an exploration of the mystery of the role. The whole idea of mystery in a performance is very much an Alan Howard invention. He started to look at the ambiguity of any given moment. Whether it was a positive moment or a negative moment he would look for the other side, at the same time; and then hold them together, so that if the line was, say, 'Once more unto the breach', even on that he would be looking for a way not only to send them back to the breach, but actually of being not quite certain whether it was the right thing to do. He was trying to catch both elements together. Now all these things, what we call up here 'positive ambiguity', we think are all part of Shakespeare."

Alan Howard himself added: "It's really also the inconsistency thing that bugged me quite a lot - that very often people were trying to make a character philosophically consistent, which is impossible. I couldn't quite understand what a consistent character was because with one's family and one's friends the last thing one was was consistent. In Shakespeare, and in all good play-writing really, the opportunity should be there for you to honour the inconsistency, because that's where the tension and the drama lie... Then of course it's got to be motivated and justified."

This rejection of a simplifying key to a part leads to the idea of 'mystery'. "Yes Peter Brook talks about that very well when he talks about a play having a secret play inside it. And I think the same goes for actors. I think that they should find something that is secret and mysterious and peculiar to the person that they are trying to portray -something you can rationalise to yourself and know what sort of components make it, even if they don't add up in a totally logical way. The strange thing is, and the more you allow it to... what's the word, percolate, no - well, sort of exist in you, it will grow and then the externals and peripheral things will be enriched and made human."

This approach goes naturally with playing fuller texts - you cannot cut a single line without scrupulous examination - and speedier playing. "We started to take phrases at a lick," says Hands, "only pulling up where a scene insisted - or an audience did. We suddenly found we were playing acres more text than before, which meant that the parts started to alter radically; because they had different things to say. Laurence Olivier's Richard III, which I happen to adore, is an hour-and-a-half version. You couldn't play that version if you played the whole text."

This in turn meant not having complicated sets, which take time to change. Hands and Howard started what was to become the history cycle with "O for a muse of fire that would ascend / The brightest heaven of invention" - Shakespeare's apology for inadequate props at the beginning of Henry V - delivered from a bare stage. "We would never have got away with that," Hands considers, "if we hadn't had the umbrella of financial problems to protect us. The fashion of that time was that people were tiring of opulence, they wanted bare boards. We were lucky... Suddenly taste has changed again, back to opulence; the depression syndrome."

Alan Howard was born on August 5, 1937, into a family of actors. His father Arthur Howard played Professor Pettigrew Opposite Jimmy Edwards in Whack-oh! and enjoyed the security of a long run in No Sex Please, We're British. His uncle Leslie was one of the few Englishmen to have become an international romantic star. His mother Jean Compton Mackenzie was also an actress; Fay Compton is a great-aunt and the novelist Compton Mackenzie was a great-uncle - and so the line stretches back, if not to the crack of doom, at least for two centuries.

His theatrical family may have given him the idea of acting professionally, but no member of it encouraged him. Howard started in the traditional way - a year pushing scenery around in rep. at the Belgrade, Coventry, and then a few small parts, the first in Major Barbara. Drama school was omitted, with no ill results. When Wesker's Roots was a success he went with it to the Royal Court and the West End, and subsequently did the other two plays of the trilogy and The Kitchen, also by Wesker. Some small parts followed at the Royal Court, a season with Olivier at Chichester, Shakespeare in Nottingham and South America - there seemed any number of directions in which his career might develop; but there was a discernible inclination towards literary plays and Shakespeare. In 1966 he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company and he has been with them practically ever since.

"You could see immediately that Alan was totally unfashionable for that period," says Terry Hands. "He spoke extraordinarily, an amazing voice, and had that princely quality of hauteur. And I liked it. This was somebody sorting out the role and not giving it a fashionable surface."

Not that he took the centre of the stage immediately. Over the next 10 years Howard proceeded to build a reputation for intense, original interpretations of secondary roles -his eccentric period: a neurotic Jaques in As You Like It, a gold jock-strapped Achilles in Troilus and Cressida -"vividly male and utterly dangerous", in Hands's phrase, "but at the same time feline and female". In the mainstream, his Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing won him an award as 'Most Promising Actor', but in a production that was not admired.

But his Hamlet (at Stratford) was a disappointment. He himself felt the production only needed a few changes. When it did not go to London, he says, "I was very, very depressed. It took me quite a long time to recover from that. I didn't talk about Hamlet, I don't think I even referred to the play for a good five years. It should have been a good Hamlet and it was not quite recognised as such.

But in the same season came Peter Brook's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, which confirmed and further developed Howard's approach. The most spectacular Shakespearian success of its time, it triumphed in America and then on a tour that took in Eastern Europe and Japan and ended in Australia. When he returned he played the lead in a strange, powerful big play, Bewitched - and it flopped. "It got scurrilous reviews, they really hated it. I stand by that pIay…"

The next year is generally agreed to have been the great breakthrough, a huge step forward and up. "I think his work changed in 1975," says Sally Beauman. "He found a new sure confidence, a new discipline. I think it was partly to do with James being born, partly to do with being away all that time."

|

The plays in which everything came together were forced on the company by poverty. Hands wanted to do the three-part Henry VI, but nobody was about to let him do Shakespeare's least popular plays in the middle of a financial crisis. So he turned to the acceptable Henry IV, 1 and 2, and Henry V. "I said, 'I'll do them with Alan" and I remember there was an outcry. Everyone said, 'He can't play Hal. He's too odd. He's not Hal, he's Hotspur."' If Hamlet had looked ideal for Howard, Henry V did indeed seem hopeless miscasting. Olivier's performance and film cast a long shadow. "Olivier presented a wonderfully complete man from the first moment; whereas I thought with the full text and the Henry IVs before it, it's a much more nervy start. It is a long Odyssey really, Hal to Henry V. He seems to have moments of security and strength and then it all goes to mush again. And then this alarming stuff with his father and indeed with Falstaff… I don't use a lot of historical facts but it is true that he was a sickly child, frail and perpetually ill. And it is true in life, I think, that such people tend to compensate by really pushing themselves." Hands reckons: "He found more in Henry V than, with respect, anyone has ever found." Howard won an award as 'Best Actor of the Year'. |

|

When the same team of actor, director, designer composer went on to tackle the Henry VIs they were met with a variation of the same outcry. "You can't ask Alan to play silly old mumbly Henry VI, Warwick's his part." Now he had become too heroic and authoritative to play the holy fool. Howard points out that no-one had ever seen the full text on the stage (not since Shakespeare himself was 30, as Dr David Daniell has estabIished). Again the main character was examined as the son of his father. "We saw the play through his eyes," says Hands. "Actually Henry VI is a very advanced man. He says: 'I think people like Warwick bashing each other over the head are ridiculous."' Howard carried on: "But he sort of allows it to happen by default, doesn't he? So that becomes questionable morally." And when Richard III uncharacteristically hesitates before murdering him, Henry starts on a terrible curse. "So the bile and the horror has perhaps always been in that man. So perhaps he's not so saintly?" The Henry VIs are minor works of Shakespeare, but again a new and more complicated figure has been uncovered.

Inevitably re-valuations of Shakespeare are going to find themselves bouncing off Stratford's own productions and traditions, but it is striking how often earlier admired performances, some too early for Howard's generation to have seen, crop up - never more strongly than with his most recent pair of kings, the Richards. They have received less than unanimous praise at Stratford. But I found his Richard II unbearably moving, the finest I have seen, finally dispelling the looming spectre of Gielgud's famous interpretation. Richard III, however, has always seemed Olivier's personal property, a brilliant comic cartoon figure that resisted the attempt to give him other facets. Howard at first seemed detached: "I think that the comedy is coming. I don't really like playing for laughs. I think there's something desperate, something awful in this play. Because we've done all the others, this awful holocaust play has to happen, this burn-up, this maggot that's introduced to eat the pus out Of the body politic. . . it's a pretty horrendous idea. And the laughs that one wants are sick laughs, followed by appalled reflection - the thing you get in Jacobean plays: 'God, what am I laughing at? That man has just pulled somebody's guts out through his bottom'... something like that."

And in that last pause Richard III turns back into nice Alan Howard and offers to ring for a taxi.

Mark Amory

The Sunday Times, 11.1.81