Production Information

|

Production Information |

|

It was only to be expected that The Bewitched would meet the usual puzzled incomprehension which most of our daily theatre reviewers bestow on major works; they go to the theatre hoping to be able to get to their offices in time to write their copy for the next morning's edition in comfort: so they like plays which are easy to categorise, to judge and sum up: hence they are bound to dislike anything which is outside their usual intellectual range, and, above all, anything that is too long and threatens to involve them in a time problem. To watch some of these dispensers of instant judgement fidget, twitch and worry in their seats on the first night of The Bewitched was truly painful. (Ironically enough they could have saved themselves the anguish. There was a strike the next day and their reviews did not appear until the day after anyway.) Who would blame these journalists, faced as they are with the problems of instant reviewing? |

|

It is unfortunate nevertheless that as a result the really great plays get the worst reception from them. It happened with Bond's Lear, a masterpiece of modern theatre which has been seen all over the world and remains in the international repertoire, but which thanks to this system, disappeared from the London stage after a few weeks. It will, it is hoped, not happen to Peter Barnes masterpiece, thanks to the fact that the RSC plays in repertoire and can maintain such a play in its schedules long enough for second thoughts and more considered judgements to take place.

Make no mistake about it: The Bewitched is a masterpiece, a work of true genius. It is grotesque, lyrical, thoughtful, full of broad theatrical effects, baroque, cruel, funny, suspenseful; a feast for intellectuals as well as a rollicking example of folk theatre. It is this very richness which is bewildering at first. Like all great works of art the play needs time to do its work in the minds of its spectators: it will haunt them for a long time, force them to think about its meaning and finally yield lasting insights.

The play tells the story of the genesis of one of Europe's greatest and bloodiest wars, the War of the Spanish Succession, which opened the eighteenth century and shaped the course of history for generations. This great and bloody war could have been avoided if King Carlos II of Spain had had an heir. But Carlos was a disease-ridden spastic and epileptic, the product of centuries of Hapsburg inbreeding. The peace of the world, the life of millions, depended on this pitiful creature's potency. The play, in truly epic style, shows the efforts, intrigues and machinations of the Spanish court to achieve this one end; the production of a successor to the throne. It shows how, in an age of religious fanaticism and superstitions, heretics were burned at the stake, witches hunted and tortured in order to induce the Heavens to produce a solution. And how, in the end, all the machinations came to nothing, precisely nothing.

A historical drama, then? Certainly, but far more than that. The Bewitched, being an examination of human motives and reactions, is also a highly topical play, a political tract for our times. It shows a grotesque misfit trying to govern a nation. Look around you: do you not see grotesque misfits determining the fate of nations from Uganda to Washington DC (and not forgetting some places much nearer home)? It shows the absurdities of power, grandees who regard their prerogatives and privileges to be far more important than the sufferings of starving millions. Are we not in the grip of the consequences of just such absurd strivings for the preservation of prerogatives and privileges (whether they are the prerogatives of lawyers and courts or unions or political office holders)? It deals with the absurd beliefs and superstitions which lead to torture-chambers and bloody battlefields. Is our world not filled with the groans of the tortured and millions of dead, victims of beliefs no less superstitious and absurd?

Such is the vast subject matter of Barnes's play: he matches it with the wealth of his invention and the sheer power of his language. The play is written in a baroque idiom of his own invention, filled with grotesque archaisms, including grammatical forms of the verb which, though they never existed in reality, brilliantly convey the flavour of the seventeenth century. There is a mixture of styles: from grand tragedy to music hall no theatrical device is spared. But this too is deliberate - designed to shock, to shatter any idea that what is taking place is merely a historical reconstruction. In some respects this is a new variant of Brechtian Verfremdung. When, as the grandees and church dignitaries decide to hold an auto da fe and to burn some heretics at the stake, they suddenly break into a rendering of 'It's Entertainment', the point that is being made is that behind all the claptrap about the saving of souls and pleasing God, there is the cynical decision to distract the populace from its starvation by the provision of entertainment. The grandees who turn into music hall performers before our eyes are shown to be no more and no less than music hall performers; the theatrical device unmasks their true nature and shows what they are really doing when they indulge in all the cant of the Inquisition.

It is a tremendous subject treated with tremendous inventiveness. And it needs a vast canvas. It is a very long play. Having had the opportunity to study the text very thoroughly before I saw a performance, I am aware of the cuts and modifications made to simplify the technical problems the play presents to its director and designer. On the whole Terry Hands has solved these with impressive ingenuity and the designer, Farrah, has created a very workable and visually stunning environment for the action. Yet the director's awareness that the play would run too long has induced him to hurry it along. This diminishes many brilliant theatrical effects that were in the author's original conception and dampens down the lyricism and poetry of the quieter passages which demand time to register their full impact.

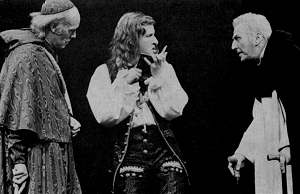

Like all truly great plays this is crammed with wonderful parts for actors: Elizabeth Spriggs and Rosemary McHale are splendidly contrasted as the two main antagonists in the intrigues over the King's body - the Queen Mother, imperious, intelligent, overpowering on the one hand and the petulant, greedy, sex-starved German princess on the other. George Claydon is a splendidly baroque dwarf and court jester - he has the wit and wiliness of a figure from a Valazquez portrait. Philip Locke and David Waller are the ecclesiastical antagonists, the lean, epicurean Cardinal versus the beefy ascetic Dominican. Joe Melia is a splendidly devious Jesuit: the twinkle in his eye could be an expression of his inherant arrogance, or it could be self-irony. Trevor Peacock contributes two brilliantly contrasted character cameos: of a Jewish heretic who bargains even on the stake, and a modish friar who stuns the King with the latest witch-hunting devices. Nicholas Selby is suitably bluff and earthy as the leader of the Queen's faction among the grandees; and Dilys Laye balances brilliantly on the knife edge between demonic character actress and music hall performer in the crucial part of the Royal Washer-woman who can sniff out the court's private lives from their underclothes.

|

But the virtuoso performance of the evening is Alan Howard's in the enormous and quite literally backbreaking part of Carlos II. Peter Barnes uses the fact that epileptics have moments of almost superhuman lucidity in the post-epileptic state to give his grotesque spastic anti-hero speeches of sudden eloquence and poetic insight. This demands an actor of immense range who can make the transition from blathering idiocy to subtlest lyricism without breaking the unity of the character; behind the disease the image of the man he could have been had he developed healthily must always somehow remain visible as a potentiality, just as the straight limbs must somehow be potentially there inside the diseased and twisted legs and arms. Alan Howard manages all these enormous tasks with elegance and ease. |

|

Martin Esslin.

Plays and Players, June 1974.