A bumbly sort of bloke, but what a

talent

He came, saw, conquered, then left to work in films.

But Alan Howard still has the power to set the stage alight.

|

For 16 years he was king and conqueror at the

RSC. Whatever the crown - Hamlet, Henry V, Richard II,

Coriolanus - Alan Howard was hailed as great, greater, greatest. It

seemed that his reign would never end. Then, in 1980, Howard abdicated, decided

there was a world elsewhere, beyond Stratford and away from Shakespeare, a

world of film and television, and something vital got lost in the translation.

These days, to theatregoers under 30, he is the myth they missed; to

moviegoers, he might be a blank if they didn't see him stripped naked and

smeared with dog shit in The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover.

Only those who witnessed him in heroic vein, tearing up those boards season

after season, will never forget it. For them, a stage appearance by Alan Howard

will always be a great event.

Great is a dangerous label for any actor to

have acquired. For a start, once you've done the Shakespeare, there are few

roles big enough or tough enough to warrant it. Second, if a part demands it

and an actor doesn't pull it off, the only alternative is to disappoint.

Richard Eyre, who lured Howard back to Shakespeare in Macbeth a couple

of years ago and in a masterful piece of casting now has him playing the

repressed and jealous husband in De Felippo's La Grande Magia, believes

that Howard remains capable of great acting. "His greatness has something to do

with a refusal to compromise. He will do nothing to appease an audience. That's

a rare and admirable quality. It takes great courage and there's a sort of

folly in it. There's also a kind of innocence about him - which is the person

that he is - and simultaneously a conspicuous bravura."

Terry Hands, whose collaboration with Howard at

the RSC resulted in one of those revelatory and electric partnerships (like

Peter Brook and Paul Scofield, Trevor Nunn and Ian McKellen, Deborah Warner and

Fiona Shaw), pins the business of greatness down to resources - "vocal and

psychological. A great actor gives all he's got, strengths and weaknesses. In

Alan, what we see is vulnerability as well as power. Alan is not just

technically skilful but hugely instinctive. He doesn't think academically or

politically or fashionably about a role, he works through it intensely at a

psychological level." |

|

Hands remembers the days when he and Howard had

babies at the same time and shared a flat, a nanny and the excitement of

keeping the RSC at the centre of the theatrical map. "Often I'd be fast asleep

and he'd come crashing in at 4am, desperate to tell me something about the part

he was playing. After an hour I'd fall asleep and he'd still be talking. I'd

see him again for rehearsals at 10.30 and I'd be shattered and he'd be clean,

polished and bright."

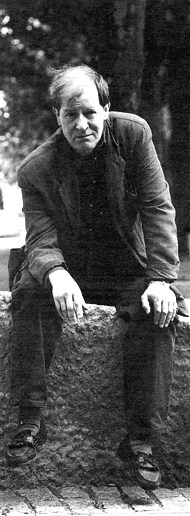

Hands also recalls how Howard could pass unnoticed

through the fans clamouring at the stage-door after a performance of Henry

V. Howard's acting involves an astonishing transformation. Off-stage, if

you didn't know better, you'd guess him to be a prep-school classics master.

His linen jacket matches his hamster-coloured hair and his nicotine-stained

fingers and the hamster-like impression persists as he blinks, shy and

short-sighted, in the sunlight, anxiously clutching an M&S plastic bag (his

stock of cigarette packs) and smiling in a glassy, wobbly way. He couldn't be

more diffident or shambling if he was playing a part. Indeed, Howard is so

low-key and downbeat, he would make Eeyore look flighty by comparison. The

effect, not that any effect is intended, is delightfully endearing.

Then he speaks and you can't quite believe your ears

because the voice is nearly as good as you get when he is more obviously

trying. Irving Wardle caught its range perfectly when he described Howard's

Macbeth. "There's no more thrilling sound on the English stage. The

sardonic croak, the lyrical caress, the one-man brass sections, the whinnying

cry of horror. They are all there." Even in normal conversation he swills words

like mouthwash, then hovers for ages around one note or on one tone, giving

equal weight to ev-er-y syll-a-ble in a sentence. It's rather hypnotic. And

it's obviously an acquired taste. Vocal magnificence to Wardle's ear can be, to

others, hollow histrionics. Howard's parody of himself. Of the same performance

Charles Spencer wrote, "He uses [his voice] like a showy soloist giving a

display of vacuous virtuosity. In the great speech at the end, when he

considers all that he has lost through his own evil, he breaks up the line

about 'honour, love, obedience, troops of friends' so unnaturally that you fear

he might have suffered a minor stroke. What's missing is real pressure of

thought or feeling behind the words."

Howard twitches a bit at the mention of critics and

grabs another fag. "One can be criticised for overdoing it and one does

care. Even if all but one of the reviews say you're good, the nature of the

paranoia is that when you go on stage you think that's the only one everyone

will have read." All of a sudden he dives into his M&S bag and pulls out an

exercise book. "I found rather a good thing that I've been carrying round," he

says. "Dickens said, 'What is exaggeration to one class of minds is plain truth

to another.' The paint stroke you use for a particular word, sentence, speech

has to impinge on somebody else's imagination. It's not just the literal sense,

it is something to do with an impression which won't be forgotten. It might

drive one person up the wall, but it might, you hope, connect with someone

else."

Despite his evident, and unusual, ability to do so,

Howard doesn't enjoy dissecting his craft. "It's blood, brains and balls -

eggs, I suppose, if you're a woman. When you try and explain it, people either

think you're loopy or talking complete bollocks. It's just something one is

passionately keen to do."

From the age of five, Howard was keen. He wanted to

be King Arthur (kings have clearly always exercised a certain pull on his

imagination) and acting was the only way he would manage it. It's a surprise,

nevertheless, to discover that this striking anti-luvvie is the product of a

theatrical dynasty. Five generations of inherited skills, experience and

thespian family tradition course through his blood (and yet he can't manage a

single "darling"). His great-great-grandfather was Henry Irving's grave-digger

in Hamlet. His uncle Leslie (Ashley Wilkes in Gone With the Wind) was a

huge Hollywood star; his father did a lot of television comedy. His actress

mother was invariably out of work, which explains the lack of encouragement

Alan encountered even while she acknowledged his talent. She insisted that he

should begin as a dogsbody scene-shifter. Which he did, though the prospect of

humping scenery for the rest of his life made him increasingly

desperate.

Then, one lucky day, someone dropped out, Howard was

required to walk on, and the rest is history plays. (In actual fact, before

making his mark at the RSC, he did his apprenticeship at the Belgrade Theatre,

Coventry; was a member of Olivier's first Chichester Festival; and did rep in

Nottingham.) "I've always felt you learnt by doing it. The more you do, the

more you find how little you know."

Self-deprecating as he is, Howard has an equivocal

relationship with fame. "However subconscious, there is some sort of desire for

fame or notoriety," he says. "It was certainly among the reasons for leaving

Stratford, that and the old cliché of wanting to spend more time with

his family. (He lives with bonkbuster Destiny writer Sally Beauman and

they have one son at university). He says he was very tired. "We did four or

five shows, working day and night. I loved and hated it. Acting is a sort of

demon, and demons are exciting and compulsive and sort of sexy, but also

frightening because there is a sort of possession and, when you're not

functioning, you begin to wonder 'Who am I? A shell? A cabbage?' It's also

frightening because I can remember doing things when I'm acting which

physically I could not do, like jumping several feet into the air. This

creature - Coriolanus - had just taken over. Which is why at the end of a show

I like to leave that character behind, have a few drinks. I want the diversion

of a completely alternate life. Pootle about, do some DIY. I liked walking the

dog, but he's just died. Can't get another yet. Too upset," he says, putting on

a silly voice in an attempt to be brave.

He's also fascinated by the different technique that

film demands. "Film works like this," he says, his fingers meeting to make a

wigwam. "The theatre works like this," and he inverts the shape. Too often,

though, the camera misses the point of Howard altogether, flattening him out,

dulling the danger. It tends to make him look bland, gormless and clumsy.

Perhaps the roles have never been right. He goes on trying, nevertheless,

forgetting fame and just enjoying the ride. Who knows, his latest part as God -

"a nice bumbly bloke" who recreates the world in seven days in a film entitled

Soup (as in cosmic soup) - might suit him better.

Richard Eyre explains that a film actor must let the

audience in slowly, express emotion almost as a stain soaks through a cloth.

Stage acting, by contrast, requires thought at the speed of light and awareness

of 50 different things simultaneously, something the mercurial Howard does

better than any actor except perhaps the super-volatile Jonathan Pryce. It's

hardly surprising, then, that Howard and film don't mix.

Still, Howard won't submit to death by celluloid. He

prefers to put his lack of success down to impatience. "If you want to be a

film star, you've got to be available and available and available and hang

around and wait while they don't get it together. I couldn't stand that. I'd go

mad. I'd go mad." But there's another problem too. "You have to sell

everything about yourself and have it marketed as part of the deal. And I'm

just bloody awful at doing it. The thing is, whatever I marketed, it just

wouldn't be true. It's the acting that's true, and if that's good, then why on

earth does anyone want to know more?"

Georgina Brown

Independent, 12.7.1995.