|

|

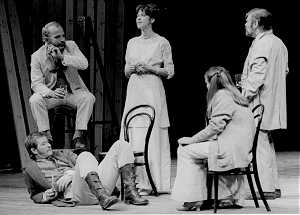

"ITS GOOD FUN living in our house," says Pavel, the dreamy scientist who is at the centre of Maxim Gorky's Children of the Sun (1905). The "fun" includes suicide, madness, a peasant uprising and a deal of heartbreak. But that kind of irony runs right through this volatile, growingly attractive play (well revived by the RSC at the Aldwych) that shows people locked into their own egos while outside the seeds of revolution are being firmly planted. It is not, however, a didactic or nakedly political play. Instead Gorky looks at the educated middle classes, with their talk of life and art and humanity, with the bloodshot eye of a satirist. In particular he captures their lack of human proportion. Pavel, the dotty scientist who spends his days rushing from one test tube to another trying to create a living organism, has a wife who threatens to leave him, a disturbed sister and is himself being pursued by a voracious widow. |

|

But when events come crowding in on him, what really obsesses him is that the refrigerator's broken down. It's like a man stopping to tie up his shoe-laces before he throws himself off a cliff.

I suppose the obvious thing to say about the play is that it's Chekhovian. Pavel and his friends pass their days talking about how wonderful life could be if only they could rise above small-mindedness and triviality. They hymn the virtues of work while behind them the yardman gets on with the task of putting up a fence. They slurp tea, fall in love and philosophise and in the background the rising classes plan the building of factories. But although Gorky has Chekhov's instinct for the restlessness of soul and impracticality of the Russian middle-classes, he doesn't have his mastery of symphonic structure. In Chekhov every line falls perfectly into place: in Gorky the rhythm is jagged, fitful and violent.

But Terry Hands' production captures that specific Gorkiesque atmosphere of rows one minute, bear hugs the next and reveals the characters in all their frenetic absurdity. Norman Rodway is splendid as Pavel, forever scuttling about his house with hands thrust deep in pockets like a demented White Rabbit. Alan Howard as a melancholic Ukrainian vet in love with Pavel's sister also resists the temptation to play for easy sympathy: he tells a joke with the slow solemnity of the humourless and rather relishes playing the role of a Hamlet-figure with a green umbrella.

Natasha Parry as a rich widow, though I didn't quite believe in the sweat under her armpits, also has the right hectic fluster and Carmen Du Sautoy as Pavel's lazily beautiful wife, Sinead Cusack as his blanched, pained sister and John Shrapnel as a noisy artist also have the right intransigent selfhood.

Admittedly Chris Dyer's set of three curling scroll-like screens suggests more a Japanese teahouse than a Russian estate and the play itself takes time to get going. But as a comic vision of Mother Russia, the evening has a nice disenchanted zest.

Michael Billington.

The Guardian, 10.10.79.