|

|

|

'Working at anything is a sort of trap, I suppose' says Alan Howard when you wonder if being associated with the same theatre company for nigh on ten years might be a risky business. 'But there's nowhere in my experience such a collection of people who seem to be equipped for .......... for the aim. Whether we get there or not.........' It's the morning after the first night of Henry IV Part 1. There's no morning after like the morning after a first night. Howard's had a bit of sleep but he looks like death and he's still got to talk to the Coventry Evening Telegraph. He twists into bodily knots in the comfy chair in Trevor Nunn's Stratford office and he agonises the concepts out in disconnected streams of thought. It's a bit like a student conversation at three in the morning, four hours after the pubs closed, two hours after you got stoned, but, like a student, Howard is thinking on his life, not trotting out formed answers, not ticking over in the sort of career where, if he thought for a moment, he'd panic. Like college, the RSC provides that wonderful security which lets you ponder before you leap into finals. And Howard, after continuous assessment through Orsino and Edgar and Benedick and Achilles and Bartholomew of the Fair and Mephistopheles and Oberon/Theseus and Dorimant in The Man of Mode and Enemies and The Balcony and Carlos in The Bewitched, is now going for the double first of Hal in Henry IV and the king in Henry V. He's just had a sabbatical year doing modern plays at Hampstead Theatre Club and a variety of TV plays. But theatre is clearly his faculty. 'Change, it seems to me, is much more likely in the theatre' he says, unmoved by the wider audiences of TV and the movies. 'I mean not just in the work one does but in the approach to it. There's a growing movement in the theatre to become more and more collaborative. We talk about directors' theatre and we used to have actors' theatre and I don't think anybody wants those. They want it to be the collaborative occupation that it really is essentially. The writer is definitely the most important person and then there are these other components that come together and try to realise the text. Now that, regardless of what is done on the floor, needs to be thought through from an administrative point of view so that you don't get the feeling that there's a sort of bloc of people who are employed and you're there by the grace of God and bloody lucky to be working. I find that's going on much more in the theatre, that thinking through. A lot of younger film-makers think in that way but capitalism isn't prepared to go along with it. In the theatre one has more chance of changing one's own approaches and attitudes. Going in another direction, for instance in the commercial theatre, one presumably becomes a household name or one has to start living one's myth and working at one's image, I think there's a great danger that you remain there and you're not actually connected to a reality. You're less susceptible to change.' Not that that kind of ossification is unthinkable in the RSC. It might have happened to Alan Howard as he progressed up the Stratford step-ladder to the juiciest plums of the Shakespeare repertoire. But in 1970 he first worked with the man he refers to simply as Brook - Peter Brook, who cast him as both Oberon and Theseus in the production of A Midsummer Night's Dream of which most of us still await the topping as the theatrical experience of a lifetime; and by 1975 the RSC itself is pulling out of a hit-and-miss groove and presenting a sustained and thought-through body of work. 'Five or six years ago,' says Howard, 'I used to think I knew what things were as regards acting. Lately I've re-looked at a lot of it and that's been largely as a result of being in association with people. The more you get to know them and the more you break through the traditional veneer of theatrical social relationships, which tend to be superficial or camp or whatever, the more you discover that actors are as real as people anywhere. By finding out about them you find out more about the business of acting, that it represents as many aspects of frailty and strength as it fulfils some technical standard. I'd thought that I had the beginnings of a blueprint of a standard of acting, that one had learned certain techniques, how to get a laugh, say, but there's a danger that one continues doing that, that if it's popular and successful one exploits it. Brook more than anybody made one re-question, made one realise that there's no point in doing things everybody knows one can do although that may be what the public or the system want you to do. Then they know you, they can identify you and they can exploit you in a situation that you're exploiting as well. It's a question of growing on and growing back too. I think there's often a terrible danger of losing the behind knowledge, because if it becomes too successful you don't look back and it just arrives at a punctuation point.' |

|

The success of Brook's Dream, as it's come to be known, led to a world tour which, along with his sabbatical and his stint in The Bewitched, kept Howard away from the Stratford end of the RSC for five years. Returning now, he's amazed at the smoothness of the organisation. 'There's been an astonishing new look at how not to f*** the actor up on the first night. Invariably what used to happen was that one worked all through the night for days, it seems to me, and at the last minute somebody said "well, ok, it's yours" and by that time the company was under the ground and they'd then got to take this space-ship off the earth. |

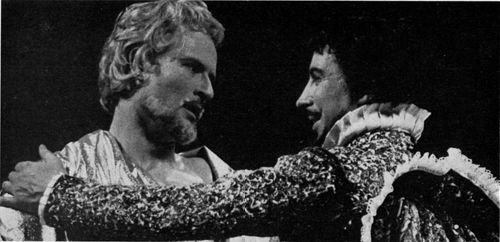

Alan Howard as Lussurioso (left) with Ian Richardson's Vendice in Trevor Nunn's 1966 production of Tourneur's 'The Revenger's Tragedy'. |

|

And of course it got two feet in the air and then sagged down because of the whole pile of garbage that had been thrown on you at the last minute. 'But this time I really take my hat off to Terry (Hands) and Abdul (Farrah) and all the technical people here. Things are about three months further ahead than they normally are. It's meant that first nights here haven't always been quite the first nights they ought to be. Aldwych openings have been better. It's played in and the Aldwych is a much easier theatre. This is a pig of a theatre to play. It's a big place, you're very exposed, the circle is too far away, the house is split so that you can't look just there and take the whole thing in. It's a difficult house. So it's a challenge. But if it's not properly organised, the actors really do suffer. And you've got the sheer welfare problems - people moving away from home and, when the weather's bad, everyone having colds and bugs and diarrhoea. This time we've survived that. Nobody winges and moans. They've actually got on with it.' Perhaps, one suggests, the Nunn regime has reached its full maturity, its prime. 'Yes. Maybe. Maybe it's the plays.' As to the plays, the Stratford season comprises Henry V, Henry IV Part I and Henry IV Part II, presented in that order, with the other Falstaff play, The Merry Wives of Windsor, as comic relief later in the year. They're all directed by Terry Hands and the history plays are designed by Farrah. 'I think that Terry has lessened his directorial concepts,' says Howard, 'and that's a measure of his development. When we started Henry V, we had certain agreed notions between ourselves about certain directions we'd go in. But if they're truly open, as happened in The Dream and in Henry V, things happen in the rehearsals which are a revelation to everybody. Providing the director is open to "Christ, I never thought of that" in the same way that an actor should be, you stand a better chance of getting a bit further on the way. I think it's a mistake to approach any of these plays assuming one's going to crack it. Because one isn't. And it would be terrible if one did crack them totally because there'd be no point in doing them again. One just wants to find a way of doing it so that people's interest is revitalised and so that the possibility of the plays' eternal future is established. One's only doing them really so that in another four hundred years' time they're done. That's certainly what Terry's moving towards. It's a risky thing for a director to do because he does lay himself open by suggesting that everybody should contribute to a lot of argument and discussion, some of which is irrelevant and some of which is destructive, and by constantly encouraging 24 people that things that they say may not be relevant to you personally but may be useful to someone else in the room, may help them on the way to finding out about what they're doing. It breaks down the old order of theatrical hierarchy. And it does take time. But once you get a group of actors who are used to it, you can work incredibly quickly because there's no suspicion and misunderstanding. The guy with five lines may be totally revealing for the guy who's saying a hundred lines. We are dealing with a communicating medium and if the people doing the communicating aren't clear about the sum of what they're doing, there's not much chance of the audience understanding. All the audience are separate and individual creatures. Why should they have to accept one point of view? Shakespeare is extraordinarily inconsistent and ambiguous and there's something in it for all of us to interpret our way. There should therefore be coming from the other side of the proscenium arch that amount of inconsistency and individuality, because that's the way the connexion is made.' The plays are presented in an order which is neither chronological in terms of composition nor sequential in terms of internal events. Howard says that 'from Terry's point of view, and from mine too, Henry V is the pivot play in the historical series. It's the odd one out in a curious way. The fact that it has a chorus gave one the opportunity to explore that play, from a company point of view, in order to establish something, hopefully a new look at that play which would then lend a vitality to the others which are simpler in some respects. I think he's going a long way towards re-looking at it. |

|

'It's a bit like the way we used to look at The Dream. The Dream and Henry V are two pops which have always been done in a particular sort of way. Either it's right to do Henry V because of circumstances - there's a war on or something - or it's not done. So there's something static in people's idea of the play as there was with The Dream, a nice little cosy chocolate-box play for kiddies. I think it's a miles greater play than that because it investigates the problem we all have of being intensely passionate about something. The way in which it's written........ it goes and then it stops, it goes again and then it stops, he keeps looking back and asking "should we be doing this?". That's the development of that man - he has to learn to come to terms with responsibility, though he doesn't really want it as none of us really do. I like finding the end first. We find the reasons for what we are now by looking at what happened in the past. I'm finding it a fascinating process. I dare say some things will alter as we get further into Henry IV. Henry V is more me, he's nearer my kind of age and development. That's as far as I've gone in my life, so it's a living thing for me. A lot of mates came last night because they wanted to start at the beginning of the story, but it's actually more interesting to start with the complete man and then go back. |

|

|

The run-in to an heroic role like Henry V doesn't find Howard working out in the gym all day or riding to hounds. 'I really find the best way to approach any role is to do with collaboration, is to do with the people you're associated with. If everyone is encouraged to contribute and not feel shy about it, so many ideas come up that it's better than reading a hundred books because they're all live people. It's actually what people say that affects me most. One is affected by what one sees or reads but when one meets somebody else who's seen it or read it, that's the reward. Out of that kind of rehearsal situation, all sorts of attitudes and references to you start to bring alive this thing that you're going to do. One didn't go around trying to assume what it was like to be a hero. I don't know what to be a hero is, really. One can read books about Alexander or Napoleon but they may have been as ordinary as you or I sitting here. Obviously Henry was struggling all the time to know things and change things and challenge things. And that we did all the time in rehearsals. |

|

|

'There were a lot of attitudes that were terribly anti the play at the start of rehearsals because of the times in which we live and the sensibilities we have. And through conversation and debate, people started to see a sense in it and realised that their very antagonism to the man or the play was revealing something that the play was asking them to look at in any case. As to training oneself, if the role becomes attached to you and there is a part of you in it, if intellectually and emotionally you get a grasp of it, the physical side follows, your body does what your intellect and emotions demand of it. You run 100 yards faster if there's a bull chasing you. But it's all there in that extraordinary text. People have extraordinary blocks about Shakespeare. But he's the supreme communicator. He's given you the words. Just use them. Use them in the way you want to use them. Eat them. Trample on it, throw it about, it won't break, it won't fall apart. Sometimes a pair of shoes, for instance, can give you a certain sort of assurance. There are a million devices that can help. But the two essential things for me are the text and what a group of people can do by questioning it. I always remember Brook saying when we started The Dream, "quite honestly, thirty heads are better than one with this man".' |

|

|

It's clear that many of the foundations of Howard's present approach were laid by his experience with Peter Brook. 'One had preconceptions,' he remembers, 'but I didn't anticipate his generosity and I didn't anticipate how akin his feelings would be to certain sorts of things one wondered about oneself. I loved his appreciation of ambiguity and inconsistency. I expected the Great Director, the Great Concept out of which one couldn't move. It was absolutely the contrary. As soon as he noticed anybody getting in any way sure of what they were doing, he'd tell them to get unsure, because the process of investigation should never cease, the questions should never stop being asked. Those words must live all the time, those words and the way they're put together are like the sea. The answer is never going to be there. |

|

|

'If The Dream had been in America, under a ........ let's say a more unscrupulous organisation, they would have made five reproductions of that production and sent them around the world as they did with Hair. They'd have made an absolute fortune. But Brook said "that's as far as it's going to go and that's what it's got to be". The whole vitality of the production was so particular that it could not be reproduced, that whole fluidity in it and the search for the answer ...... well, they'd have had to have provided an answer and it would have become a stereotyped, stark, stiff thing. In a way, The Dream still lives for those who were involved in it and maybe those who saw it. It wasn't a full stop in any way. And that's the whole point of theatre. It's our imaginations that continue it and we pass it on to our children, embroider it and embellish it in our own minds and it's as important as something your grandfather told you when you were a little boy which you remember and embroider and embellish till it becomes you. Which is the whole continuum from wherever it was we started. And all the garbage of institutions and politics and religion that is foisted on us is not worth so much.' W. Stephen Gilbert Plays and Players, July 1975 |