Mikhail Bulgakov knew all about absurd,

tragic twists of history - he satirised Stalin and paid the price. Critic Of

The Year Michael Billington hails a neglected Russian gem

Catch 22, comrade

The National Theatre may not have done anything

special this week to celebrate the Brecht centenary. But at least they are

reviving Mikhail Bulgakov's Flight in the Olivier. And the first thing

to hit one about this extraordinary satiric epic, banned before performance at

the Moscow Art Theatre in 1928 and only premiered in 1957, is how it deals with

classic Brechtian themes: exile, pursuit and the difficulties of survival in

chaotic, dangerous times.

Bulgakov himself knew a thing or two about survival.

In 1930 he famously wrote to the Soviet authorities begging for emigration or

employment. He was phoned by Stalin himself in what he took to be a hoax-call,

given a minor post at the Moscow Art Theatre and ensured his posthumous fame

through two masterly novels, Black Snow and The Master And

Margarita. Unlike Brecht, he never reached an accommodation with state

power. What the two writers share is an ironic temperament and a fascination

with endurance in the face of historical confusion.

That is the running theme of Flight, which

Bulgakov described as "a play in eight dreams". In those dreams it follows the

capricious fortunes of a group of White Russian soldiers and civilians from

defeat in the Crimea in 1920 to exile in Constantinople and Paris. It deals, in

particular, with four characters: Charnota, a Cossack major-general rescued

from total destitution by his gamblers' instinct; Khludov, the autocratic White

Army chief of staff ludicrously encased in military discipline; and Golubkov ,

a St. Petersburg professor hopelessly in love with Serafima, the deserted wife

of a deputy minister.

What Ron Hutchinson's agile new adaptation brings

out, however, is Bulgakov's gift for making serious points through black farce

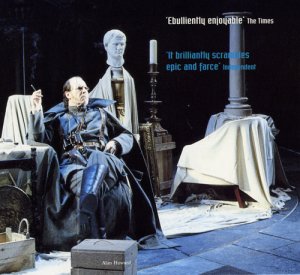

- Joseph Heller comes to mind as well as Brecht. As played by Alan Howard,

Khludov is an insane butcher who has sent whole regiments to their death and

who arbitrarily hangs anyone who crosses his path. Yet it is Khludov who points

out to his absconding commander in chief that it is always idiots who rise to

the top and who, forced to earn a living in Constantinople by pumping out music

from a barrel organ, remarks in wonderment, "civilian life always seemed so

complicated". What Howard captures perfectly is Khludov's paramount absurdity

and automaton-like nature - as Bergson pointed out, comedy always starts when

man reacts to life like a machine.

Clearly the play is intended as a satire on the White

Russian leaders. But what makes it so intriguing, and what prresumably incited

the Soviet censors, is its regard for their resilience, cunning and luck. If

Khludov survives by his myopic disregard for reality, Kenneth Cranham's wily

Charnota does so by trusting to his gambler's antennae. He outwits the Reds by

posing as a pregnant woman, bets on cockroach races and, in the play's funniest

scene, wins a million dollars at cards off a fellow émigré

in Paris.

|

In many ways, the play is alien to British

experience: it is about the tenacity of the refugee-spirit and, in the end,

about the Russian longing for home. But it survives, theatrically, through its

quicksilver shifts of tone and its pervasive irony. It works very well in

Howard Davies's spectacular production, for which Tim Hatley has designed a

brilliantly flexible set: one dominated by a panelled back wall that opens up

to become a Crimean palace occupied by mobile, white-sheeted statuary or a

bustling Turkish street brim-full of carpet, hookahs and birdcages.

Davies, however, rarely allows the production's

monumental scale to obscure the quirkiness of character: Michael Mueller as the

love-smitten professor shows how an idée fixe triumphs over a

collapsing society. Abigail Cruttenden as Serafima embarks on a life of

prostitution as innocently as if she were going out to do the shopping.

|

|

And Peter Blythe is especially funny as the fugitive

commander in chief who fusses about the prose style of a newspaper report even

as the White Army faces defeat. That moment eptomises the strength of

Bulgakov's blackly sardonic play. He sees history as an insane mixture of the

tragic and the absurd - a lesson ultimately learned after years of suffering at

the hands of the Bolshevik victors.

Michael Billington

Guardian, 14.2.98.