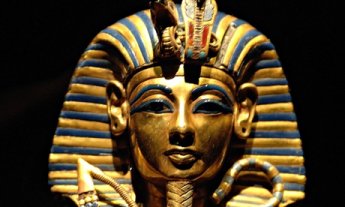

Unearthing the truth … real and fictional characters mingle in Beauman's tale of Tutankhamun. Photograph: Frank Trapper/Corbis

|

|

Unearthing the truth … real and fictional characters mingle in Beauman's tale of Tutankhamun. Photograph: Frank Trapper/Corbis |

Every few years, historians take exception to novelists encroaching on their territory, and historical fiction gets a battering in the press. The rise and rise of Hilary Mantel, herself an able defender of the writer's right to write about whatever she damn well pleases, has put a temporary stop to these bad-tempered outbreaks. The truth is that a great deal of fiction is historical; most writers who write more than one novel will, at some point, set a book in the past. Historical fiction remains ever-popular as a genre, and historical fiction readers are among the most engaged of online reading communities. Many writers are attempting to tap into this passionate conversation by producing a stream of historical fiction sequels to once-contemporary novels, such as PD James's take on Pride and Prejudice, the recently televised Death Comes to Pemberley; Sally Beauman herself embarked on this most meta-fictional of readerly responses through her Du Maurier sequel, Rebecca's Tale, set in the 1950s.

And, of course, the past has all the great stories. One of these is Howard Carter and his search for the tomb of King Tutankhamun, which Beauman has tackled in her new book, The Visitors. Set in Egypt in the 1920s and London in the present day, this hugely readable novel tells the story of Carter's long years of toil in the Valley of the Kings through the eyes of a 10-year-old English girl recovering from a bout of typhoid to which she has lost her mother. Her academic father retreats to his Cambridge college and it is left to Lucy's temporary guardian, an American of suitably doughty proportions, to restore her young charge to health on a lengthy excursion to Egypt. At Shepheard's Hotel in Cairo Lucy makes friends with a whole host of archaeologists, their wives, their servants, and, most crucially, their children, a clever mix of real and fictional characters that includes Carter and his patron, Lord Carnarvon. After a fairly lengthy setup, the party decamps to Luxor, where those most glorious of bodies are buried.

The story of Carter and Tut is one with which we are largely familiar; here Beauman explores the intriguing question of whether or not Carter broke into the inner sanctum of the tomb prior to the arrival of the Egyptian authorities. This is the central drama of the story - the moment Carter first laid eyes on the boy-king and all his gold, the gold sarcophagus, the gold chariot, the huge and chaotic piles of gold and jewellery that Carter found. But our narrator, Lucy, is not present at this scene - whether it happened illegally in the middle of the night, or in the full blaze of the desert sun and the world's press days later - and this is part of what doesn't quite work in The Visitors: the sense that the real action is elsewhere. Lucy's new best friend Frances, the daughter of the American archaeologist, Herbert Winlock, who was also engaged in digs in the Valley at the time, spends a great deal of time explaining archaeology and archaeological history in a manner that feels unlikely even for the most precocious child. And Lucy's own family story, including her difficult relationship with the governess in England who persuades Lucy's cold and unappealing father to marry her, also suffers in comparison to that extraordinary moment in the tomb.

What do work very well are the contemporary sections, when Lucy, now almost as old as an Egyptian tomb herself, takes a great deal of cranky old-woman pleasure in thwarting a young documentary-maker who wants to find out what she knows about Carter. Here the writing is at its entertaining best. Beauman's portraits of the unclubbable outsider Carter, obsessed with finding the tomb that he knows in his bones could be inches away from where he is digging, and Lord Carnarvon, ailing and frail, on the verge of withdrawing funds from Carter after many fruitless years of digging, are also vivid and illuminating. Egyptians are scarcely present in the story, though the new and pressing Egyptian nationalism features in the background, including the government's efforts to gain control over archaeological finds. And above it all floats the gold deathmask of King Tut himself, endlessly touring the world's museums.

Kate Pullinger

The Guardian

8.3.14