|

|

|

No words of mine can adequately convey the theatrical, visual, and above all the spiritual splendour of Terry Hands's production of Henry V, which opened the RSC Stratford-on-Avon season last Tuesday. Henry V is a most difficult play, to which the temper of the time is altogether hostile. It is full of pageantry, of shining armour and of banners; and today pageantry is something to which we are instinctively unsympathetic. Mr Hands has dealt with our imperfect sympathy by an invention as daring as it is brilliant. He begins the performance by putting his cast into sweaters, football gear and jeans: and then at the precise moment when the audience is utterly weary of this drabness he changes them into costumes that illumine the theatre. The play's second great contemporary handicap is that it glories in being English. Now to glory in being Welsh, Scottish or Irish is permissible, and even laudable. But to be proud of being English is generally regarded as bordering on indecency: it makes the delicate blush. A sensitive colleague voices the opinion of the majority of sophisticated playgoers when he describes Henry V, with stern disapproval, as "patriotic tub-thumping." Mr Hands has done more than conquer this almost universal prejudice: he has used it to make his Henry V richer and deeper than I have ever known it to be before. |

|

He has particularly noted that Henry's claim to France was doubtful: and even more he has been affected by that scene on the night before Agincourt when Henry wanders amongst his troops, and in disguise talks to them of their troubles, and is met by the man who tells him what wounds and tribulations war brings to common soldiers.

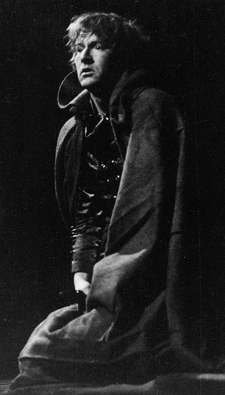

The magnificence of Mr Hands's production lies simply in this, that his Henry has no need of the instruction. In this incident he used once to be played as a great king and noble warrior comforting his people: but today we see him, Alan Howard plays him, as a man sorely in need of comfort himself, and knowing that he will have to do his best in a terrible situation without it.

For Mr Howard's superb, and I had almost said eclipsing, Henry is not a natural soldier. Whenever war approaches, doubts and distress cloud Mr Howard's face: his Henry is made for other things than war. He fears war: but being in it he acquits himself like a pride of lions, and out of the depths of his anguish he utters some of the most ringing and thrilling calls to valour ever heard in a theatre.

|

But it is at a great cost that Henry conquers both himself and his opponents: a cost seen most vividly when Harfleur surrenders. Henry faces the audience, and when he hears the news that there will be no further battle the relief of his tension is such that he very nearly breaks down. He is like a man saved at the eleventh hour from hell. The production is packed with brilliancies: the glitter of the three French nobles in their golden armour just before battle: the scaling of the wall at Harfleur: the kindly gentleness of Emrys James's Chorus: the figure of Oliver Ford-Davies's Herald writing quietly through the night: and the reconciliation of Henry with the soldier who had insulted him. Most brilliant of all perhaps is that Henry V is to be followed, not preceded by Henry IV. For if Mr Hands can show us how this man became what we now know that he manifestly was, this will be among the greatest seasons in Stratford's history. Harold Hobson Sunday Times, 13.4.75.

|

|