|

Aside from the fact that he will be up on stage

with Howard, he is vague about the content of the show: "It's our first day. We

don't know exactly what will happen...."

He slopes off to the loo, leaving Aukin

improvising: "It's very clear that it will be very much a theatre performance

and very different from the broadcast...." Hitting upon a comparison whuch has

Howard chipping in with his support, she adds: "It's really a very exciting

form of storytelling. That's what one wants to achieve, storytelling in

performance. It's not a dramatisation with props and costumes."

Such is the pleasantness of the group that

there is no apparent discomfort when Logue later chooses to nip this particular

idea in the bud. "I'm not inclined to stress the storytelling element of the

text too much. It's narrative but there is no story in a way - the Greeks went

to Troy and it was a disaster. Everyone knows what happened........ But I don't

really like things when they just depend upon suspense."

He is more fascinated in character. "There's a

big philosophical question as to the difference between a myth and an epic. The

deconstructionists have done better work on this than anyone. In folk tales

there is very little character. You're handling not even stereotypes but very

simple elements like a wolf and a man in a forest. Everything then depends on

what happens. But in a dramatic narrative, including epic, you're handling

character, and the Iliad is where characters were invented. Two thirds

of the Iliad is people speaking. The other third is people fighting." A

throaty laugh starts to disrupt his flow. "That's all there is talking and

fighting!" he splutters.

Logue has had a chequered past, as editor of

True Stories in Private Eye, as a protestor for CND (jailed once for

three weeks), as aauthor of an erotic novel, as screenwriter for Ken Russell on

Savage Messiah and as occasional actor - he played the Player King

opposite Jonathan Pryce's Hamlet at the Royal Court. Even his poetry has led

him into strange areas - he put together a compilation of reputedly filthy

limericks and once provided poems for a Findus Foods calendar of "lovely

ladies".

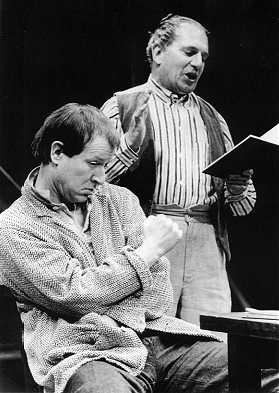

There is an air of unpredictability in him even

now, but one-time RSC actor Alan Howard puts the conversation back on an even

keel agreeing reverently that the interplay of personality in Kings is

as exciting as any what-happens-next momentum. "The confrontations and the

suspense between characters - that's a fantastic dynamic."

Logue becomes serious himself. He finds another

layer of interest in the workings of the creative team itself. "Poetry readings

have a rather poor reputation, rightly, and it's partly because the readers are

unprofessional; they give the impression they are doing the audience a

favour..... But also most poetry readings are not critical events. They are

full of self-indulgence. I've found that when I'm working on text with Lianne

and Alan it's a critical event, because I alter the text in relation to what I

hear. I start off with one text and I finish with another." That chuckle

again.

Logue himself admits that from the director's

point of view "a lot of writers are so vain about what they've done, it's a

nightmare having them in the bloody theatre", but as it is, Howard and Aukin

find his presence crucial. "When the actor and writer know each other, it's a

terrific inspiration for an actor to say words which have been written by

someone who is there with him," says Howard.

That the text should not be graven in stone is

hardly surprising considering Logue's magpie-like enthusiasm for picking up

inspiration from wherever he can find it. Howard talks grandly about the fact

that "you can feel Milton, you can feel Shakespeare, yet the poem is absolutely

of today." Logue prefers to acknowledge his translating predecessors by saying:

"Of course I look at Pope, of course I look at Chapman - to see what they did,

to see if there's anything I want."

Kings and War Music surprised

reviewers by their modernity, the controversially anachronistic images. There

are references to horses rising "as in dreams, or at Cape Kennedy", or to "a

helicopter whumping in the dunes", to the eyelets on the armour of Ajax as akin

to "runway lights". Logue says he feels no pressure to update images to add in

the odd Gulf term for example - but he comments: "If you're reading a good

newspaper and there's a good image you just take it. It might come from the

Gulf war. It might come from what's going on in Croatia. It might come from a

pub fight down the road." "Seen one war, seen them all," adds Aukin

drily.

Since his marriage to critic Rosemary Hill, the

64-year-old says he has become less lazy, but even reciting his working day

seems to tire him."I now go to work like any other working man," he titters. "I

start at about eight and I finish about half past 12 or one. Then I do a bit in

the afternoon. But I get tired - though not too tired to do other things like

shopping or paying bills or trying to get people to pay me more money - all of

which is very exhausting. |