|

|

Like Amsterdam's specialist brothels, Restoration comedy was formerly tolerated as a libertine entertainment on the understanding that it made no contact with the flow of normal life. One of the main achievements in the past decade of classical production is its release from this ghetto by the elimination of that cordon sanitaire once known as 'Restoration style'. Plenty of productions exemplify this process, but none more completely than Terry Hands's version of The Man of Mode which admits not only the human content of the play but allows it a sense of continuity stretching back to Shakespeare and forward into our own time. Rarely has the RSC's classical-contemporary policy been more fully vindicated. This is claimed as the first London revival of the comedy since 1766, but Prospect Productions mounted it in Yorkshire a few years ago, and the memory of that show, with its standard parade of bloodless gallants and simpering mistresses, heightens the sense of what has been gained at the Aldwych. Comparatively decorous though the text is, The Man of Mode is hard to take as an artificial comedy as its fun is unusually cruel. The intrigue turns as least as much on the tactics of dropping women as picking them up; and Dorimant, the principal lover, acts as much from sadism and ruthless vanity as from desire. |

|

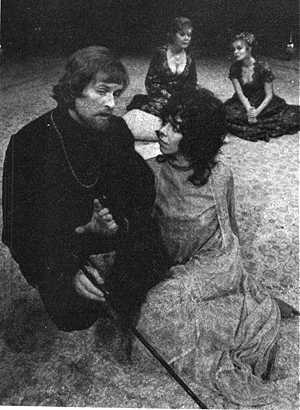

Timothy O'Brien's beautiful set derives from a familiar modern living toy, a framework of suspended steel balls, here magnified into a constellation of silver orbs hanging over the stage and gliding into new positions for changes of scene. The costume, long dresses for the girls, and velvet suits (worn with broad brimmed hats) for the men, further locates the piece in a cool playground for the modern peacock generation whose dances and pastoral lyrics go to a John Dankworth score. Here Dorimant (Alan Howard) voluptuously starts the day, relishing the prospect of rejecting a mistress and stripping off to drop into his morning bath to await news of the latest virgins in town. Howard plays Dorimant with a crooked auburn-bearded grin and a body twisted by his own intrigues; you never question his capacities to get things moving, but there is no appeal whatever to sympathy and you relish his humiliations as much as his successes.

This is important, because the full gesture of the production is one of benevolence. In this sense it joins hands, say, with Mr Hands's production of The Merry Wives; an action in which many mean things happen, but which finally develops into a celebration of fecundity from which no one is excluded; not even David Waller's Old Bellair, who goes through the show pinching the bottom of his son's beloved, or Vivien Merchant, who camps up the discarded Mrs Loveit into the purple-gowned likeness of a Sunset Boulevard has-been.

The clue to the interpretation may well have been the character for which the play is best remembered: Sir Fopling Flutter, the first of the Restoration's line of Francophile clowns. The point about Sir Fopling is that everyone wants him to do his thing; he is a cause of entertainment, not irritation, to the other characters. And from the first moment of John Wood's performance, torpedoing his white walking stick into the wings, it is clear that he is to be source of much more than malicious mockery.

|

Francophile snobbery is one of the basic comic cliches; but by the end Wood has earned sympathy even for that (as in his delight at finding the one English follower in his retinue starting to speak French). It is a lovely, highly vulnerable performance, which reestablishes Mr Wood as a major asset to the company. Helen Mirren's Harriet, tousled amid her immaculate companions, hurtles through the action as an embodiment of rebellious natural life; never more so than when she and Terence Taplin mime a tender courtship scene for the benefit of two match-making elders. Irving Wardle The Times, 14.9.71. |

|