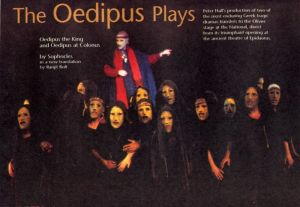

|

In Oedipus the King the stage-pictures

are overpowering. Alan Howard's doomed Oedipus occupies a long platform that

juts out over the stage and, at the last, he appears in a hollow-eyed mask

which makes him look like one of Bacon's cardinals. The blind, mud-caked

Tiresias is led on stage by a boy with a rope in an image of Beckettian

dependence. And when the Chorus recognise the horror, a single masked face

turns towards the audience in a state of inexpressible grief.

But Hall also brings out the philosophical

contradiction at the heart of these plays. "Our lives are ruled by chance,"

claims Jocasta; and, in one sense, Oedipus is the victim of fate. But Sophocles

also shows that Oedipus has a restless curiosity and heroic dedication to

truth. In Howard's performance you sense a passionate zeal to know

himself.

The paradox of existence comes out even more

strongly in Oedipus at Colonus where in Dionysis Fotopolous's setting,

the sacred grove is implied by a single Godotesque tree. "Never to have been

born is best by far," cry the Chorus in Sophocles's most quoted line. But the

action is also a tribute to human endurance, to the possibility of loyalty and

affection and to the fact that, while we suffer in the present, "there was

suffering yesterday". Hall's production perfectly preserves that balance

between pain and stoicism.

In short, the plays come alive for a modern

audience. Howard, having articulated a rising arc of emotion in the first play,

in the second brings out the ironic humour underlying Oedipus's suffering. And,

under the masks, there are striking contributions from Suzanne Bertish as the

agonised Jocasta, Greg Hicks as the blindly prophetic Tiresias and Pip Donaghy

as the shiftingly ambiguous Creon. Judith Weir's music also has the supreme

merit of heightening the emotion without overpowering it. But the triumph of

Hall's production is that, while using the methods of antiquity, it makes these

plays accessible and shows how human suffering is constantly countered by

fortitude.

Michael Billington

The Guardian, 19.9.96 |