Nunn's 'Hamlet': a report from

the kitchen

Ronald Bryden at Stratford - from read-through to

first night.

|

This is not so much a review as a report on an

experiment. It's a perennial battle-cry in the wars between critics and

theatre-folk that we show-tasters judge a play by a single sampling. In the

artificially frought conditions of a first night. We decide its future in three

tense, unnatural hours, as brutally and superficially as the eleven-plus

decides a child's. Instead, it is urged, we ought to go into the kitchen and

see the real work of a play's making: the whole evolving process, from

read-through to première, which is the true life of a theatrical

production. I've been doing just this with Trevor Nunn's new Stratford

Hamlet. I'm not sure I've any firm conclusions to bring to the argument,

but it's been one of the most fascinating experiences of my life.

|

|

Strictly, I can say, what the theatre-folk ask isn't

possible. A working London critic, seeing three or four plays, simply hasn't

time to follow any production through all its days and nights of rehearsal. I

managed to snatch one day to hear Nunn's initial talk to his company, outlining

his intentions. Four weeks into rehearsal (there were six), I managed to steal

six days to watch the stage at which, lines pretty well mastered, the cast

began to commit themselves to their characterisations. One week before opening,

I saw the last run-through before the play moved on to the big Stratford

stage.

But long before that, I knew there could be no clear

outcome. The show-folks' point was proved: I'd never again be able to see the

first night - any first night - as a thing in itself, to be judged in

isolation. It would be part of the whole process I'd glimpsed of trial, of

rejection, of deepening and growth, exploring the hundreds of Hamlets possible

with that cast alone. On the other hand, I'd never be able to judge that

process, not with the detachment necessary for criticism. I was hopelessly

involved, an accomplice, willing it, Nunn and the actors to succeed.

I think they have - Thursday's opening night cheers

seemed to bear out that this is one of the best things the Royal Shakespeare

has achieved under Nunn's direction. To some extent, seeing the play set and

dressed for the first time, I was finally able to weigh his total design

against his intentions, and found it brilliant. But on the whole, I can only

report and explain. That, I suppose, is what theatre people really want, and

for once it seems peculiarly appropriate.

In his talk Nunn explained that for him the key

scenewould be the play within the play, the key line Hamlet's 'Suit the action

to the word.' For him, Hamlet was a study in alienation: the gulf

between thought and will, will and performance. By the players, Hamlet the

thinker is taught how to feel and perform, to bridge the gap between inner and

outer worlds in action.

He didn't mention R.D. Laing, but this should go down

as the Laingian Hamlet. When the lights go up on the furred Court of

Denmark, Hamlet is the one black figure in a blaze of bridal white: the one man

questioning that all is well in the best of possible worlds, based as that

world is on death, incest and falsehood. His madness is not just feigned, it is

a Laingian escape from a society built on lunatic deceptions into the lonely

sanity of private truth. Between the blacks and whites of public and personal

morality, his will is puzzled, until the players burst with a torrent of colour

on to the bare Elizabethan platform Christopher Morley has made of the

Stratford stage.

It sounds arbitrary, dangerously like claiming a

once-for-all key to the labyrinth of the play. Perhaps, but it breeds

marvellous complexities. In the black, avenging cowl of Denmark's scourge and

minister, Hamlet is play-acting, unable to kill Claudius. Stripped and

pummelled cruelly by his enemy after Polonius's murder, he is tamed, stunned

into conformity. A white, brainwashed figure, he departs for England, but now

the fighting in his soul is over. He will play this society's game with it:

deceive, smile and kill.

In such a reading the key soliloquy is not the black

and white alternative of 'To be or not to be.' It is 'Oh, what a rogue and

peasant slave am I': the speech in which Hamlet, envying the player king his

painted passion, wrestles agonisingly with himself to separate imaginary,

histrionic emotions from real ones, to dredge up from the depths of his being a

true response to his mother's adultery, his father's murder.

In fact, Nunn has turned the play into a commentary

on the process I watched in its rehearsals. Alan Howard has always been one of

the Royal Shakespeare's most fascinating actors, intelligent to a fault in his

refusal to take the simple, unambiguous line of direct feeling through any

role. He is a brilliant elaborator, an infinitely fertile inventor of ironies,

jokes and defensive strategies for implying emotion by denying it.

When I joined the fourth week of rehearsals, this was

how he was playing Hamlet: as a glittering, sardonic concealer of his genuine

feelings, the most adept Machiavellian in a Machiavellian court. As a verbal

swordsman, the Renaissance avenger chuckling over death's jest-book, he was

impressive but glacial - I thought, gloomily, that this would be a Hamlet

definitive in a kind I had no wish to see.

But there were still gaps in his characterisation,

holes he walked round or through, muttering or throwing away the lines while a

significant hush fell over the rehearsal hall. They were the lines where Hamlet

is not acting: the soliloquies, 'Give me the man who is not passion's slave.'

'The readiness is all.' Tactfully, the other actors waited for him to show his

hand, pressing him only where their own playing required answering violence to

spark from. But it was clear that his performance must be the tent-pole, to

whose height, and no higher, the production would rise.

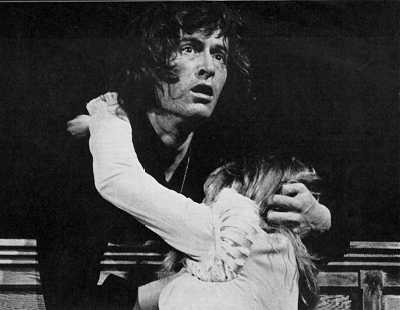

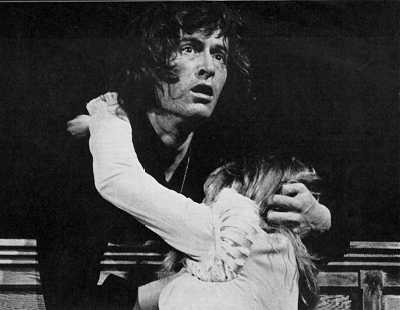

Gradually, as I watched, he mastered his reticence.

Slowly elaboration fell away, the sardonic camouflages and dazzling escape

devices. His performance grew more and more still, and, as it did so, amazingly

younger. It was as if he was stripping from himself not only years, but the

defensive armour, the competence to hide the child in the adult, which they had

brought. The jeering glances, the sharp small-toothed smiles diminished. In

their place emerged a dark, smouldering stare of misery, a sudden, dismayed

fall of the mouth, like a child who has been slapped.

I see now why actors feel this is what critics should

pass on. This is their real work: the slow, painful mining of themselves for

the emotion we normally stifle, dragging them to light, so that, watching, an

audience is compelled to feel those extremities we avoid in life, to discover

in sympathy the naked natures we bury in social masquerade. But I don't think

anyone who saw Howard on the stage last Thursday could fail to recognise the

work he had done; that he had gone far beyond any performance he's previously

given, to become not merely an actor to watch but one to reckon

with.

There are other fine things in the production: Brenda

Bruce's Gertrude, aware from the closet scene onwards that she has married a

murderer, and frozen with horror and pity for him; David Waller's Claudius,

brutal, commanding but unstrung by the loss of the woman he killed for; Helen

Mirren's Ophelia, victim of the same false society Hamlet hates, following him

into madness so that she too may tell it the truth. But having seen them in

rehearsal, individual achievements dim beside the collective one of mutual

trust in which their Prince could perform his labour of self-discovery and

exposure. Trevor Nunn has proved another point to me: this is how stars are

made.

Ronald Bryden

The Observer Review, 7.6.1970.