Wildfire at Midnight

Trevor Nunn's swaggering production of The

Revenger's Tragedy reaches London, at long last, after its 1966 Stratford

premiere. Here are two families - one common, one ruling-class, headed by a

great Duke - entangled in one of those Italianate vendettas which fascinated

Jacobean London. Vendice, head of the common family, blames the Duke for the

death of his girlfriend and father. The Duke's wife has three sons by a

previous marriage: one of them has recently been charged with rape. Their

mother wants to seduce her husband's bastard. Beside stepsons and basterd, the

Duke is also endangered by his heir - who wants to seduce Vendice's sister. The

author (Tourneur or Middleton) plunges us into this wild situation - which he

calls 'wildfire at midnight, gunpowder in the court' - making his actors tell

it in quick, difficult verse. "I am past my depth in lust," says the Duke's

heir, "and I must swim or drown." The audience, too, sink or swim in his

whirlpool: it is the director's job to sort it all out, without being a bore.

Nunn succeeds brilliantly, using spectacle not for its own sake but to

illustrate the story, to illuminate the marvellous text. The words are

paramount. That is why Nunn's production surpasses the National Theatre's

gallant failure with The White Devil - a comparable and, perhaps, even

finer revenge-play.

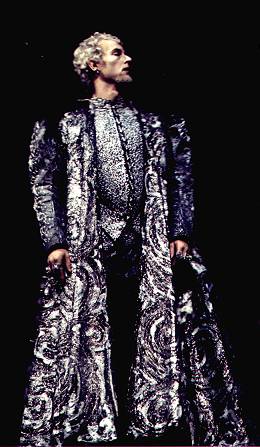

Nunn begins with a dumb show. The glittering, silvery

courtiers of the Duke's household surge forward from a deep black box,

brandishing masks and torches: as they swish in patterns about the stage, like

brilliants juggled on black velvet, we get a clue about who's being raped,

who's in charge, who's paying court to whom. (Although the Aldwych environment

offers more intimacy and immediacy, this dumbshow was even better on the

Stratford stage, which is deeper, and permits the use of real torches, smoking

and stinking.) Now the author takes over. Vendice, the revenger, in Hamlet

black with a skull, describes his courtly enemies - and they silently introduce

themselves to us , as if they were in church, bowing as they cross themselves:

we, the audience, are treated as the altar, the eyes of God. Each of the seven

male principals (unchanged since 1966) has his own way of moving, his own

distinctive sculptured outline, a triumph of the subsidiary arts of designers

and cosmeticians.

|

This hell-hole seems a real world. Each prince

has his own followers, in his own style: we know the hierarchy and the

factions. These Shakespearians speak the language as though they were born to

it. They don't 'send-up' the savage jokes: they think they're funny. Ian

Richardson, the twice-disguised revenger, operates with three Jacobean voices:

posing as a malcontent thug for hire, he has the dark, melancholy tone of a

Jacques; disguised as a courtier, he sounds as bright and silly as his own

Bertram; when in earnest he uses his fine personal blend of the Gielgud quiver

and the Olivier yelp. The three women - evil noblewoman, corrupted mother and

pure sister - are all poignantly played: but I'm out of sympathy with both

author and director in the womenfolk scenes, especially the two episodes of

mother-punishment. Nunn has built up the Duchess's expulsion from court into

something needlessly sadistic, from a mere hint in the text. The author turns

insanely puritanical when dealing with the sexuality of mother and sister. He

has stopped trying to alienate us, to make us think: his punitive earnestness

gives me the creeps. Still, it's his play, and Nunn has given him his

head.

D.A.N. Jones

The Listener, 4.12.69. |

|