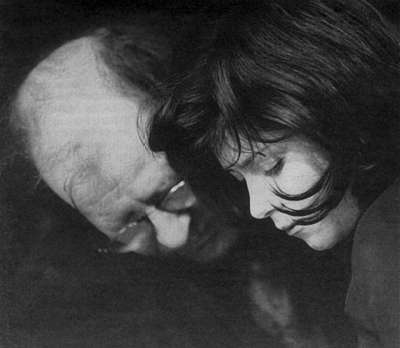

INTERVIEW When he is not playing kings, Alan Howard does a nice line in sexual depravity - and never more so than in the Almeida's new Lulu. Maureen Paton met him

|

At first glance, Alan Howard seems too ascetic a performer to play Schoning, the newspaper editor in thrall to Anna Friel as Wedekind's eternal courtesan Lulu. Howard, after all, is the man who got in The Guiness Book of Records for playing more Shakespearean kings than any other actor in history and whose magnificently metallic delivery has been compared to the sound of a bugle. Then one remembers the scenes of Howard's frenzied naked couplings with Helen Mirren in kitchens, lavatories and the backs of meat-vans for Peter Greenaway's arthouse gangster movie The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. Suddenly everything slots into place: when it comes to portraying abject enslavement to base sexual appetites, this bespectacled, sandy-haired six-footer knows his onions. The audacious quality of Wedekind's two plays Earth Spirit and Pandora's Box, conflated by Nicholas Wright's new Almeida Theatre adaptation under the title of Lulu, reminds Howard strongly of that Greenaway project, one of his rare forays into film. "I still find Wedekind's blatant amorality quite shocking; no matter how liberal we might be, we tend to draw the line somewhere, whereas the line is very rarely drawn here. It's shockingly funny," he says. "And I remember reading Peter's script for The Cook and being frightened by it; by the end, I was shaking with horror and excitement. The film was very Jacobean, a quality not unlike Wedekind. We filmed at Elstree and it was freezing, standing around with no clothes on and being hosed down by an actor playing one of the kitchen staff." He pauses and gives the squeezed-lemon smile that makes Howard such an intriguing performer. "But it was worth it for the character to have this wonderful affair with Helen Mirren." |

|

Like Mirren, the imp-like Friel is an actress of no little sexual power. Howard rather compounds the first impression of an absent-minded, unworldly professor, however, by admitting that he "didn't actually know Anna's work" when he first agreed to do Lulu. Having played Henry Higgins in what one critic termed "a near-manic debut at the National", he was particularly interested in the potential of Wedekind's drama as a very dark twin to Pygmalion.

"Lulu was obviously an abused child. Her father did a deal with Schoning when she was a five-year old flower girl: she was passed around and taught depravity so that she has become a master of it. And Schoning is the one person she can't stand being rejected by, because he has been her tutor, father figure and lover. He's quite an enigmatic figure."

As is the 63-year old Howard, one of those gifted Nearly Men whose career vagaries tantalise. The great-nephew of the novelist Compton Mackenzie and the actress Fay Compton, and the nephew of the matinee idol Leslie Howard, he began as a stagehand and worked his way up through the rep system without bothering with drama school.

With his beaky nose, fastidious mien and intellectual's horn-rim glasses, the young Alan Howard was a Jean-Luc Goddard lookalike of whom great things were expected in the wake of his Theseus/Oberon in Peter Brook's legendary 1970 Midsummer Night's Dream. At the RSC, he found the great roles that suited what Terry Hands has called Howard's "princely quality of hauteur".

Unlike such contemporaries as Anthony Hopkins, however, Howard never really transported those epic characteristics to the big screen; as he once remarked: "I was never going to be a Meryl Streep figure".

On the small screen, where his distinctive presence can occasionally seem hammy, he descended to voicing dog-food commercials.

"The RSC seemed the course to tread, and I stayed for 16 years. Afterwards I was just known as a classical Shakespearean actor and nobody would ever consider me for anything more modern," he now says, "I did feel trapped by that; it happened to a lot of actors in those days when they stayed longer than they do now, although Ian Holm managed it very well by getting into film.

"There comes a certain time in one's life when one is never going to be a film star, but it would be nice occasionally to get a really good cameo. It's sort of fun to do and sometimes it pays grown-up money. Nowadays the theatre you really want to do doesn't pay the rent; basically, actors are subsidising the work."

|

Nevertheless Howard remains a theatre animal to his fingertips, with an air of restless intelligence about him that suggests he might become quickly frustrated by the stop-start nature of film work. Three years ago he played Vladimir in Waiting for Godot and King Lear for Peter Hall at the Old Vic and now feels that he "would like to have another go at both. I had done the Oedipus plays with Peter, and Oedipus at Colonus has a Lear-like quality. So he really persuaded me, even though I kept wondering whether my Lear was a bit premature." Howard believes that the theatre still offers more freedom for an actor: "Anything that is recorded, like film, becomes plastic and is somebody else's property. In theatre, there's still room for manoevre; if it's been well directed, there will be a degree of leeway and moments of discovery every night." By coincidence, Howard had been cast as Schoning once before, back in the late Eighties. It was a proposed National Theatre production by Howard Davies of an Angela Carter adaptation but it came to naught. Jonathan Kent, who is directing Lulu, was unaware of that when he wrote to Howard and offered him the role. Kent saw in him a particular quality: "Alan has an immense authority as an actor and as a man," says Kent. "There's a blend of power and sophistication in him." |

|

Despite being a diabetic since the age of 20 ("I was determined not to let it stand in my way"), Howard has only once dropped down a few gears to do some undemanding telly work for a few years when he was helping his partner, the novelist Sally Beauman, bring up their son James.

Theirs is a thoroughly equal partnership, worlds away from the exploitation of Lulu by every man who meets her. "It will be interesting to see what the feminist reaction will be to Lulu; its quite a fraught piece. So I think Sally and I will probably argue once it's on."

|

Lulu press night on March 19th at the Almeida at King's Cross, Omega Place, N1. Maureen Paton The Times, 13.3.01. |

|