Article / The Sunday Times / 24.7.77.

Review / The Sunday Times, 19.12.76. Below.

Review / The Shields Gazette, 21.2.79.

Article /Newcastle Evening Chronicle, 27.2.79.

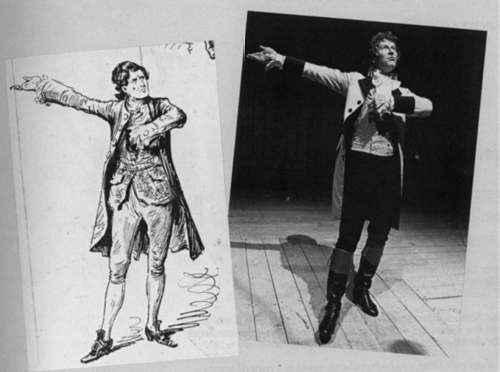

Edward Compton in Wild Oats

|

Article / The Sunday Times / 24.7.77. Review / The Sunday Times, 19.12.76. Below. Review / The Shields Gazette, 21.2.79. Article /Newcastle Evening Chronicle, 27.2.79. Edward Compton in Wild Oats |

Pure gold, champagne, moonbeams and caviarWith Wild Oats (Aldwych) the Royal Shakespeare Company have struck gold. Mere gold, do I say? Nay, gold and oil at once, and rubies and diamonds to the utmost profusion, mingled with vintage champagne, lightly chilled, caviar is there, also, of the finest quality, sprinkled with a few drops of juice from lemons picked by the soft white hands of beautiful virgins on the southern slopes of Mount Olympus, nor does that list exhaust the powers of this amazing and multi-purpose spring, for from it pour, in addition, limitless quantities of moonbeams, ortolan's tongues, perfectly-cut cucumber sandwiches, waterfalls, sonnets sung by angels to the sound of silver harps, and an army with banners that glitter from afar in the noonday sun. It will, I think, be apparent from my introduction that I enjoyed myself at this play. What may not be immediately discernible is the fact that anybody who does not enjoy himself at it must be dead, and indeed to a considerable extent decomposed. Wild Oats is a farce by an altogether forgotten Irish-born eighteenth century man of the theatre, John O'Keeffe; first performed in 1791, it seems that it has not been revived for more than eighty years. Well, it has now. |

|

The story it tells is of dazzling ingenuity, you must pay very close attention whenever new characters enter, for they will at once proceed to explain a further twist in the plot, like the people in Agatha Christie or Wagner, and it would be a pity to get lost. Mistaken identities and cross purposes proliferate like midnight mushrooms; the characters are woven, one by one (sometimes two by two), into a glittering web of inter-relationships; the scene flickers hobgoblinally from place to place (there is an enchanting set by Ralph Koltai, in which the same door keeps changing position); threescore bricks of plot are piled recklessly one upon another until it seems that they must tumble in hopeless confusion to the ground, yet stand as secure as St. Paul's; there is love at first sight, the overthrow of wrong-doers and the triumph of virtue, the reconciliation of sons with estranged fathers and the last-minute discovery of long-lost children; there is a choleric Admiral, and his ex-seaman valet, who talk entirely in nautical metaphors ("The worm of remorse has gnawed his timbers"), a beautiful Quaker lady (the author's attitude to her sect is astonishingly enlightened for the period, for she is portrayed as perfection itself while being allowed to remain entirely within the severe framework of her beliefs), and a gallant actor who is the centre and hero of the play, and who sprinkles throughout his conversation, with inexhaustible profligacy, perfectly apposite quotations from Shakespeare.

|

It is generally supposed that the English drama languished for more than a century after the force of the Restoration had exhausted itself; there followed a desert punctuated only by a few oases like Goldsmith and Sheridan. Yet O'Keeffe, it appears, was enormously prolific from 1773 to 1813, and this play is better than She Stoops to Conquer (his first play was actually based on Goldsmith's work and called Tony Lumpkin in Town), being funnier, more ingenious and , though also sentimental, much more firmly in control of the sentiment; in fact I swear it is as good as all but the very best of Congreve and Sheridan. But it was lying forgotten for decades until now: what other treasures are there in O'Keeffe's work, and how many of his contemporaries might also now be looked over with advantage? Certainly he has nothing to learn from even the best of earlier or later farceurs for intricacy of plot, humour of dialogue or charm of character. And he has something, at any rate to judge by this play, which the Feydeaus and their like, and indeed the Restoration dramatists and the Ben Traverses and their like, largely lack: a great humane gusto, a sense of harmony and decency and optimism, an ability to leave an audience weak with laughter yet realising that if they had done no more than smile they would still be weak from happiness. |

|

Clifford Williams's production is of a lightness, wit and rapidity that between them leave praise gasping in the rear, he has done nothing so superb on the funny side of the street since his famous Comedy of Errors in the early Sixties. Norman Rodway as the exploding Admiral is a joyous creation, a plump puppet come to glowing life; Joe Melia as his servant, Lisa Harrow* as the beautiful Quakerette and Patrick Godfrey as her hypocritical steward, give performances of lovely, full-bodied juiciness.

But the greatest of these is Alan Howard as the hero. If Hamlet was angry at actors who tear a passion to tatters, he would have loved Mr Howard, who with flawless grace puts the passion together again. The elegance and swagger of his playing (he is , incidentally, visibly and audibly enjoying every minute of it) are the eighteenth century at its finest (it is worth remembering that Wild Oats was first performed in the same year as The Magic Flute), and he, in his turn, has done nothing with such consummate insouciance since, as Oberon, he hung upside-down by the back of his knees from Peter Brook's trapeze and swung out over the front stalls while chatting happily to Puck.

Whoever dug this masterpiece out for The Royal Shakespeare should be knighted at once; at once. Meanwhile, I declare that there is not to be found a more entirely delectable entertainment pitched betwixt Heaven and Charing Cross.

*The role was later taken over by Sinead Cusack.

Bernard Levin.

The Sunday Times, 19.12.76.

|

After rehearsals had started it was discovered that Alan Howard's great grandfather, Edward Compton had played Rover in Wild Oats, with great success.

Edward Compton (Mackenzie) and Alan Mackenzie Howard as Rover in Wild Oats. |