Witchcraft

Double double helping

Hannah Arendt, speaking of the perpetrators of

the Holocaust, coined the phrase "the banality of evil"; behind witchcraft has

always lain an effort to project banal, familiar evil on to exotic

scapegoats.

But all the broomstick business does not make

witchcraft an easily dismissible phenomenon. After all, belief in witches has a

long and distinguished history: as Sir William Blackstone, the father of

English jurisprudence, chillingly declared, "to deny the possibility, nay the

actual existence, of witchcraft and sorcery, is ..... to contradict the

revealed Word of God". |

|

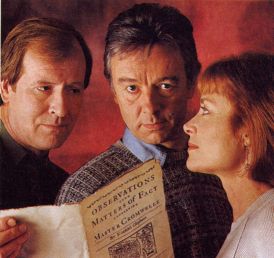

Good witching stories, among which, despite some

obvious flaws, I would number Witchcraft (BBC2 last night and tomorrow at 9

pm), Nigel Williams's screenplay based on his 1987 novel, may or may not end up

suggesting that witchcraft is metaphor; but all must convey a strong and

tangible sense of evil.

Good, modern spooky tales also have a tendency to be

playful and self-undercutting. Williams achieved this by constructing a highly

ingenious plot, whose central character, Jamie Mathieson (Peter McEnery) is a

professor of creative writing scripting a film about Ezekial Oliphant, a

17th-century witch-hunter who hanged his own wife and mistress as witches

before revealing his own commerce with the devil.

Mathieson decides to consult his old history tutor,

Alan Oakfieldl, on historical detail, only to find that Oakfield has become

unhealthily obsessed with Oliphant himself. These multiple layers and

connections allow Williams to weave a dense web of parallels and ironies

between past and present, fiction and reality.

This might all have seemed just clever

and intriguing, had it not been for the chilling sense of infection by past

evil which Alan Howard brings to the part of Oakfield. Dotty academics seem to

be Howard's speciality at the moment: here was a Higgins who had discovered not

a new vowel-sound, but the Evil One.

Witchcraft's director, Peter Sasdy, has

worked for Hammer, and sometimes overdoes the things that go bump in the night,

especially at Oakfield's improbable Jacobean Cotswold manor. On the whole,

though, he creates the right ambiguous atmosphere to keep us guessing about

just where the epicentre of evil is located. Enjoyable performances come from

Dorian Healy as a bone-headed student director and Georgia Slowe as a seductive

harlot, who might just be a witch.

At the centre of this story, however,

yawns a disturbing hole. Just what sort of person is McEnery's

scriptwriter-professor meant to be? An effortless charm seems to make him

irresistible to women (Lisa Harrow's Mrs Oakfield and the harlot), but what

feelings and motives does he have when he beds them?

It is impossible to tell from McEnery's

low-voltage performance, and the apparent self-immolation of Oakfield in a

burning folly left me worried about the drama's ability to sustain its

menace.

Harry Eyres

The Times, 15.12.92