|

'The RSC is not yet at the point where we can

prepare a production months ahead - with discussions, preparation, and work

with the other actors. Often the rest of the cast are abroad or working in

London right up until the first rehearsal. The main advantage is that you know

the work of the other actors, or rather you don't, but your relationship with

them is allowed to develop in a way that isn't easily achieved outside the RSC

with an ad hoc company.

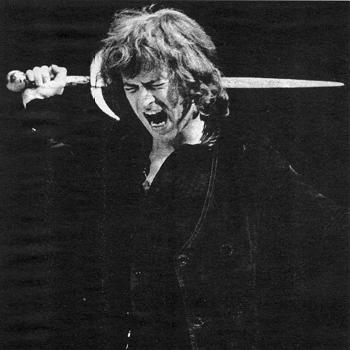

'Trevor Nunn first suggested my playing Hamlet

after my Jaques in As You Like It. And later I spent three days

discussing Hamlet at Cambridge when I was playing in Dr Faustus

there. Trevor gave a clear picture of the kind of society he was interested in

presenting - but he realised that the performance would finally depend on the

individual personality of the actor playing Hamlet.

'Every actor is able to identify with some

aspect of Hamlet's character - but this is often done at the expense of the

whole, the complete personality. I became involved in the many facets of the

man, the incredible range of his intellectual and emotional life, his

magnificent and very proper inconsistency. I found that Hamlet could only face

the situation he is in by being an actor, constantly changing his masks and

various personae. Hamlet responds above all to immediate situations - it's this

rather than reflective detachment which makes him unique. He takes every

situation to the furthest point it will go - the breaking point.'

To turn Hamlet into an 'actor' himself,

assuming different roles and personalities at a moment's notice, is certainly a

remarkable solution, and the play scene became a momentous turning-point in

Howard's interpretation. For this Hamlet has lost himself amongst the

appearances of the real world - and is unable to locate its true meaning or

purpose: 'Hamlet has been given to this kind of enquiry long before he meets

his father's ghost. For such a man to say he is going to "feign madness" must

be a deep cause of concern to Horatio. The latter has reached a position of

stillness and tranquillity in his relation to the world.

'But for Hamlet - where is the dividing line

between assumed madness and real madness? He is trying to find a link between

reality and seeming, truth and acting. Thus he is capable of losing control -

of killing Polonius without knowing what he is doing. If Horatio, afterwards,

asked him what he had been doing that night, he wouldn't have been able to give

a coherent answer. He forgets about Polonius immediately after the killing -

it's gone out of his mind. In the final scene, when he has gained a maturity

and kind of serenity, it might be that Hamlet is the only sane person on the

stage, and the rest of the court, who are "performing" are mad - or not,

depending on your definition of madness. "Mad" is such an imprecise,

unscientific word. Claudius uses the term as a convenience - so he can forget

about the problems of Hamlet. He casts Hamlet as the court jester.'

Howard explained that Trevor Nunn had attached

great importance to Hamlet's university education at Wittenberg. It was the

Lutheran university and Hamlet would have returned to the

Catholic society of Elsinore impregnated by the 'new philosophy',

claimed Howard. 'Hamlet refers to himself as a "scourge and minister" of heaven

- he has returned from Wittenberg with the protestant idea of individual

responsibility in his mind. Claudius is the other side of the Catholic culture

- eat, drink, and be merry for tomorrow we confess. When, in the prayer scene,

he tries to come to terms with himself, outside the confession box in the

protestant way, he can't succeed.

'The strongest influence on Hamlet is, perhaps,

his dead father. Obviously he had been a stern, austere Catholic king. In other

words, Hamlet had a very unsatisfactory relationship with his father which

predates the play. He has a mum problem, but it's the dad problem that

fascinated me. Why had Old Hamlet sent his son to Wittenberg - not only the

university of Lutheran ideas, but also of political dissent - the revolution?

Did the Old Hamlet suspect Claudius and send Hamlet away to hide what was going

on from him? We never resolved this.

'When Hamlet returns to Elsinore, Ophelia has

blossomed and quite naturally they fall in love. We had a long discussion about

whether they made love together. Trevor finally didn't think they had. Helen

Mirren (who played Ophelia) and I both did. But probably in secret - a short

slot, bringing an added tension to their relationship. When Hamlet first sees

Ophelia in the nunnery scene she is playing a role which infuriates him. He

starts playing a similar cool role ("I loved you not") - which suddenly makes

Ophelia reveal her true feelings of love ("I was the more deceived") - but

Hamlet interprets this as another role, not the truth. So he loses

control. Just a few honest words would have saved the situation. But they

communicate on different levels - Hamlet mistakes reality for seeming.'

Howard sees the relevance of Hamlet as

integral to the Prince's doubts about the values of the world in which he is

living: 'It's common to our own world - an individual who has learnt a certain

amount, a kind of wisdom, suddenly faces a situation where his values don't

apply any more - he sees people acting in other contradictory ways. He loses

his absolute and the development of his personality is affected. This is what

the "Rogue and peasant slave" speech expresses (Howard's choice amongst the

monologues) - a desire to reconcile seeming and truth.' |