A Midsummer Night's Dream, on tour

(Sally Beauman, who travelled with the company

in Europe and the United States, edits and writes this Flourish, reporting on

some of the difficulties and reactions the company faced.)

A Girdle Round About The Earth

Gabi saw the Peter Brook production of A

Midsummer Night's Dream in Budapest last autumn. The tickets were very

expensive and, in any case, impossible to obtain. Those that hadn't previously

been allocated to Party officials, theatre workers and Ministry high-ups had

been sold out long before. Gabi wanted to see the play so much that she

travelled up from the country to Budapest, and pushing her way through the

throngs of people at the ticket office, managed to charm one of the ticket

collectors into finding her a standing place; she got it in return for two

packets of Romanc cigarettes, and was squeezed into a place at the front of the

stalls. She had no seat, but propped herself up on Milos Jansco, the film

director, who hadn't been able to get a seat either. Afterwards, she wrote to a

friend about it: "The performance was something out of this world. When it was

over the whole audience jumped to their feet and clapped, standing, for half an

hour. Not one single person rushed out to get their coats from the cloakroom. I

am quite serious, half the audience was in tears........ I don't know what it

means to see a performance of this kind in Britain, but here it is as if one

had achieved the impossible. People look at you, point at you, and say: 'He was

there. He saw the Royal Shakespeare Company'....." |

|

The world tour of A Midsummer Night's Dream, which

started in England last August, is now on its final three month stint. When it

finishes, this coming August, the company will have played for a year in

thirteen different countries, and over 30 different cities. When Gabi saw it in

Hungary in October, it had already played in London, Bristol, Southampton,

Berlin, Munich, Paris, Venice, Belgrade, Milan and Hamburg. It was going on to

Bucharest, Sofia in Bulgaria, Zagreb, Cologne, Helsinki, Warsaw, Cardiff,

Liverpool, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington D.C. For the last three

months of the tour it will go to Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Adelaide,

Melbourne and Sydney. There is still a remote possibility, for the circuitous

negotiations continue, that it may finish up in Peking. But whether or not it

makes it to China - it would be the first theatre company from the West ever to

do so - the tour has still been an extraordinary one; the longest tour of any

one production ever mounted by the RSC, and the first attempt to send one play

into the lion's den of so many different cultures.

It all started last July, in hot humid weather in

Paris, with - appropriately enough, Midsummer's Day falling in the middle of

rehearsals. Peter Brook gathered the new Dream company together at the Mobilier

National - a vast cold echoing building on the left bank, where Brook works

with his experimental theatre company. Some members of the company had been in

the original production, though for the most part they were now playing

different parts: Alan Howard was still playing Theseus/Oberon; Philip Locke was

still playing Egeus/Quince, Terence Taplin was still

|

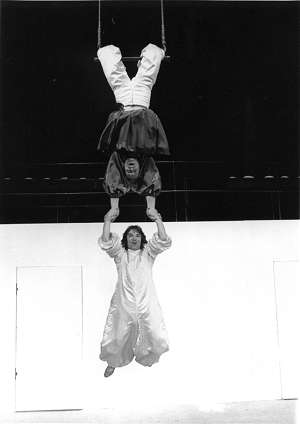

"After I came out all I could think was,

God, why didn't I become an actor? It must be such fun on the trapezes."

British Ambassador to Germany. |

playing Lysander. Barry Stanton was now playing

Bottom (he used to play Snug) and Hugh Keays Byrne was noe playing Snug (he

used to be the most hirsute of the fairies). But the rest of the cast was new:

Gemma Jones taking over as Hippolyta/Titania, Robert Lloyd as Puck, Jennie

Stoller as Helena, Zhivila Roche as Hermia, Richard Moore as Starveling,

Malcolm Rennie as Snout, George Sweeney as Flute...... it was a company of

people who weren't used to working with each other, and who came from widely

differing theatrical disciplines, who had five weeks to recreate a production

that had - rather dauntingly - been lavished with more superlatives by critics,

here and in New York, than any production since the Brook/Scofield King

Lear.

"But what we were trying to do", said Brook, "was not

in any sense to produce a carbon copy of the original. That wouldn't have been

possible, and anyway no one wanted to do it. Rather we wanted, within the

framework of the original production, within the shape that the play physically

had, to explore it again, through the responses of a very different set of

people".

There were an awful lot of practical things that

could go wrong, and most of them did. People got ill: during rehearsals Terry

Taplin broke both ankles and was in a wheelchair - out of the production until

America; Jennie Stoller broke her toe; Hugh Keays Byrne broke his thumb

(twice); Barry Stanton lost his voice; in Cardiff five people got 'flu. In

Eastern Europe the lorries carrying the set broke down; practically everywhere

there were union difficulties of one sort or

|

"The trouble with touring is that

everyone in England forgets you exist. Here I am in all these marvellous

places, but as far as my friends are concerned, for a year I'm out in the

sticks". Gemma Jones. |

another with local theatre workers. Firemen were

officious (in Paris they sprayed Titania's red feather with fire proofing

liquid that made it moult). Foreign theatres created their own problems: some

had appalling sight lines (though in San Francisco, where the gallery on stage

was invisible from the top balcony, it didn't prevent the top balcony seats

from being sold out). In Washington D.C., with humid 80 degree heat outside,

the theatre was like an oven; but it turned out no one at the brand-new

multi-million dollar Kennedy centre had the authority to turn on the highly

sophisticated air-conditioning system; for that permission had to be obtained

from the Bureau of Parks. Problems were created simply by the stresses of

constant travel: where do you find the energy to run up and down ladders, and

swing from trapezes when you've just moved, after a tiring flight, to the

second new hotel of the week, the second new country, the second new theatre?

And when you know that after three nights you'll be moving on to another

one?

How do you find the energy to get up and go to a

Press conference in the morning, facing a battery of cameras, and questions put

through an interpreter, when the night before you were at an embassy reception

drinking the Ambassador's excellent champagne? How, as Hugh Keays Byrne put it,

do you face another woman at another reception, who says to you (with some

earnestness) "Now tell me, how do you manage to learn your lines?" Or

the American lady who came up to Alan Howard at a party in Pasadena, all smiles

and much Indian jewellery: "Now you must advise me, Mr. Howard. I have four

children and they all want to go on the stage?"

|

"It's a problem of feedback. You need

response desperately - what are they feeling out there? - but you can also have

too much. To go to a reception and answer questions about the play you've just

performed, sometimes it's good, other times you just want to clam up. You get

exhilarated and you get drained: I still don't know quite how you balance out

the two, you just do". Alan Howard. |

The answer, of course, lies partly in the play

itself, and the extraordinary resilience of the production, which has managed

to go on changing and developing. "It hits high spots", as Gemma Jones puts it,

"and ssometimes it drops off badly, but so far we've always managed to pull it

back together again" - and partly in the responses of the audiences which have

been - particularly in Eastern Europe - consistently responsive and

warm.

Only in one place in Europe - Paris - was there any

system of simulataneous translation for audiences. In Germany, particularly in

Hamburg, where the company felt it gave the best performances, it was clear

that the audiences understood English fluently (they laughed at quite obscure

puns one would forgive an English audience for missing).

|

"How do you catch the plates - is it

magnetic?" - Students at Los Angeles (or everyone

everywhere!) |

In Venice, where the company played at the exquisite

Fenice theatre, the audiences arrived late (sometimes performances didn't begin

until 9 pm) and were noticeably slower to warm up. In Eastern Europe, even in

places like Bulgaria, where no English company has performed for 35 years, and

where certainly, however well they knew the play, large sections of the

audience didn't speak English, the response was quite extraordinary. Gabi was

writing about seeing the play in Budapest, but what she wrote applied equally

well to Bucharest, Belgrade, Sofia, or Warsaw. In Bucharest, students who

couldn't get tickets for the performance, were smuggled in theough the dressing

rooms to watch the play from the wings. In Sofia, where, as usual, there was

not a seat to be obtained for any performances, students were packed in,

sitting and kneeling and standing in the elaborate wooden structure that

theatre had behind the proscenium arch, so the company were playing to an

audience out front, and an audience above their heads, most of whom could

hardly see the actors, but who never shuffled or stretched for three and a half

hours. At the end of these performances the audiences went wild: they stood up,

they threw carnations onto the stage, they built up the applause into a

rhythmic slow hand-clap (a mark of approval in Eastern Europe) which would

sometimes go on for as long as half an hour, with the company joining in,

clapping and stamping their feet in time with the audience.

One of the companies major worries was what would

happen to the play, after the stimulus of

|

"It's a year out of your life. When you

start you have no idea what that means, travelling with the same people, living

in each others pockets, moving from hotel to hotel. It places enormous strains

upon people, even strains on the play. I get through by living from day to day.

I don't let myself think about how much longer we've got to go." Hugh Keays

Byrne, In Eastern Europe, a third of the way through. |

travelling, and playing constantly in different

countries, when they opened in America for a six-week run in Los Angeles. And

certainly the atmosphere there was very different. The Ahmanson Theatre, in the

recently built Music Center in downtown LA, is a daunting place, a great white

temple of culture, where the audiences all arrive by car, where there are no

surrounding restaurants or bars to give a feeling of humanity to the place. The

first-night audience were swathed in furs; very Hollywood. "Don't mind them,

dears", said the rather camp chief dresser , who'd worked there for several

years. "They're Hollywood. They always sit on their hands". And to some extent

they did. Although the production broke box office records - no mean feat in a

theatre that sits 2,100 people, over a six-week run - the audience response was

certainly

|

"I love touring. I like arriving in a new

theatre and explaining the set-up to foreign technicians through an interpreter

who doesn't know any of the technical terms. I'm the scapegoat, the father

confessor, the school master, the analyst: that's OK. It keeps me on my toes".

Hal Rogers, Tour Manager. |

slower and less warm than in Europe; half way through

the last act the early exodus for the car park would start. But still the

response, from students in particular, was amazing: one group from the

University of Santa Barbara made the journey of over 100 miles twice to see it

in LA and then,

|

"I've got my family with me, and that

keeps me going. There's two constants - them and the play. If they weren't

there I don't know what I'd do. The play would still be the stable thing, but

the rest of the days, in a foreign place, would be very empty". George Sweeney,

who travelled with his wife and two small children. |

when the production moved north to San Francisco,

made the even longer journey there to see it again.

Critical response to the play varied enormously. In

America the reviews were almost uniformly good and almost uniformly dull. "I'd

prefer", said Barry Stanton, "to have someone who took the trouble to knock the

production really hard. I wouldn't mind, so long as I felt that they'd been

sitting out there and they'd experienced something of their own. I don't mind

someone hating it - in fact it can be helpful, provided they can explain why

they felt the way they did". The most anti review came from Stanley Eichelbaum

of the San Francisco Examiner. After some prosy ramblings - "the production is

quite exciting".....three actors do approach the play like professionals - he

concluded. "Brook's highly praised production doesn't live up to its

reputation.....almost none of the activity on stage relates to Shakespeare's

play".....but he never explained why. In Europe the reviews were far less

tepid, and far more literate: at least critics there were prepared to go out on

a limb. In Rumania they took exception to the play's bawdiness: "Peter Brook's

show is not only erotic, it is, without reason, licentious and sometimes even

pornographic", wrote one critic. "We find scenes on the brink of vulgarity,

licentiousness and even obscenity", wrote another, which delighted Peter Brook.

But for the most part the reaction was one of exhilaration and stimulus:

"Brook's production", wrote a critic in Budapest, "is not just the topmost peak

of contemporary theatre, it offers a glimpse of tomorrow's stage art". "You who

have a ticket", wrote a critic in Helsinki, "you don't know how lucky you are.

If you are unable to use it, for God's sake don't throw it away, but give it to

someone who has perhaps lost faith in the theatre".

The 1972/73 World Tour: 31 cities, 307

performances, seen by approximately 450,000 people.

Sally Beauman

Flourish, the RSC Magazine,

22.5.73.