More Reviews

Shades of the golden boys

|

There is gold in Frank McGuinness's new play

Gates of Gold at the Gate. It is the gold of memory, a softly glowing

patina on a piece of extravagant and voluptuous furniture; exactly the sort of

furniture, in fact, that crowded number 4 Harcourt Terrace, dust and exuberant,

in the days it was inhabited by Michael Mac Liammoir and Hilton

Edwards.

The play, McGuinness emphasises, is not a

biographical sketch of either of the great men, or a chronicle of their lives

together. But he does not deny, nor could he, that Gates of Gold is

based on the lives of Ireland's greatest theatrical lovers. |

|

Edwards and Mac Liammoir were unique, defying

convention at a time when they could have paid dearly for it, superb in their

arrogance and coquetry, mischievous, passionate and devoted to their art and

their adopted country. They were our Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, our

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

That Mac Liammoir at least was also a fabricated

persona of breathtaking impertinence only adds to the legend. This breathtaking

impertinence, though, does not form part of the character of Gabriel, living as

best he can through his slow journey to death in Gates of Gold. He is

impishly extravagant in speech and gilded memory, but somewhere in his

frightened heart he is Shakespeare's John of Gaunt, unsure of his place in

history, and longing in spite of himself for a conventional epitaph.

The other characters swirl around him in various

degrees of compassion, affection, and predatory intentions. Conrad, his life's

love, remains stolidly stoic, almost a straight man to his vaudeville comedian.

His sister Kassie is an uncomfortably warped mirror image, her re-inventions of

herself less credible, less elegant, colder. Her son Ryan, seduced in times

past by Conrad, is seen by his dying uncle as the personification of betrayal:

yet he cannot loathe him as he wishes to. And Alma, his nurse, uses her stolid

ability for compassion as a reparation for private torment, the death of her

twin brother in a car crash.

McGuinness weaves all of these elements together with

skill and finesse; yet somehow the play seems to skirt the fullness of passion,

as though the playwright were afraid of being overwhelmed by his subject. Not

that it is stilted or dead: merely it seems he has found it necessary to bank

down the fire to protect the chimney. And one would have preferred a reckless

blaze.

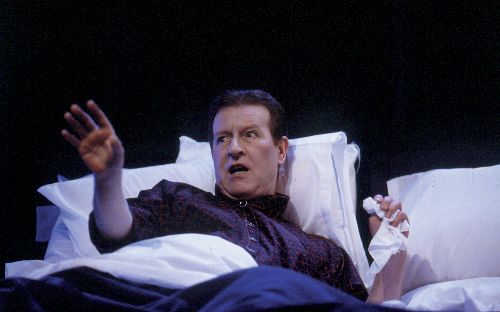

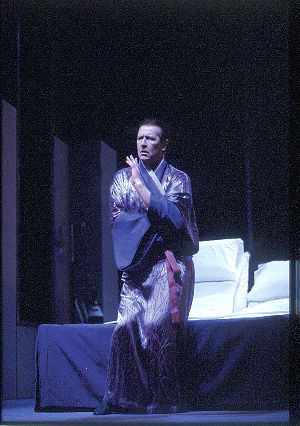

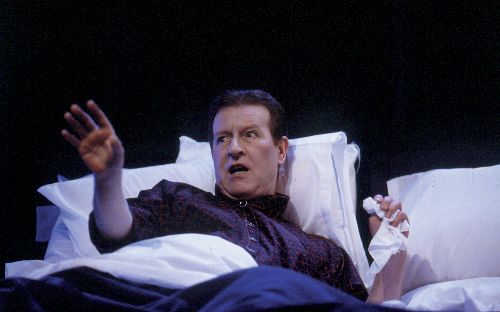

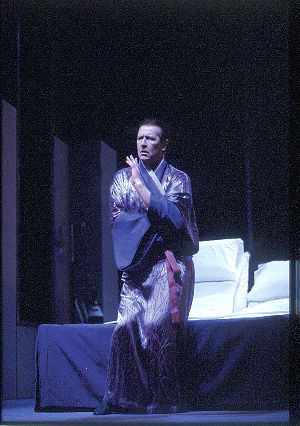

Alan Howard's dying Gabriel is a triumph of layered

and diverse emotion; Richard Johnson's Conrad, perhaps because of the way his

character is written, is somewhat shadowy; James Kennedy is suitably unsure and

petulant as Ryan. Rosaleen Linehan's Kassie and Donna Dent's Alma both play

rather edgily, the periphery of their characters seeming to affect their

performances.

Patrick Mason's directorial stamp is immediately

recognisable: a combination of intelligence and subtle empathy. And there is a

wonderful art deco set by Joe Vanek, although his costumes for Rosaleen Linehan

seem at variance with the period. Lighting is by Paul Koegan.

Emer O'Kelly

Irish Sunday Independent, 5.5.02.

Ghosts in

the half-light

Outside Ireland, you have to be of a certain

generation and/or an avid theatregoer for the name Michael mac Liammoir to mean much and an even more dedicated

follower of theatrical fashions to have a clue about Hilton Edwards.

In Ireland, though, these two actors have been

accorded near-mythic status. As the founder members of the Gate Theatre, Dublin

- which swiftly rose from its inception in 1928 to become the country's

unofficial second national theatre after the Abbey - they bestrode the Irish

stage like colossi. Their story is all the more remarkable for the fact that

Edwards was an Englishman.

Now, this multi-talented actor-manager partnership,

which was rooted in an intense personal relationship, has been revisited in a

compelling, witty but perplexingly oblique new play by Frank McGuinness,

beautifully directed by Patrick Mason.

Oblique because, though manifestly about the pair,

Gates of Gold says everything in the half-light of fiction. Edwards and mac

Liammoir are not named directly; instead, we are presented with Conrad and

Gabriel, who talk of their beloved theatre and the gates of heaven, but not the

Gate Theatre outright.

Gabriel is dying in bed, while his companion hovers

beside him or in the next-door sitting room. This looks like the hour of mac

Liammoir's final curtain in 1978, but Joe Vanek's very Nineties-looking

interior bats away literal interpretations.

By eschewing pure biography, McGuinness is able to

confront the fractious as well as the affectionate aspects of this

off-the-record gay marriage, while emphasising the transient nature of

theatrical celebrity, always a potent metaphor for man's mortal

condition.

|

Yet, so rich was the life both men led, you

yearn for more authentic detail and anecdote. Here, we're confined, as it were,

to the closing speeches of a full-blooded five-act drama. Alan Howard's gaunt,

bed-ridden Gabriel lets loose Wildean witticisms with mesmerising, sour-faced

disdain ("dying is remarkably like being stuck in a traffic jam through

Limerick"), but he can only supply faint, camply self-mocking echoes of the

histrionic, larger-than-life figure so many revered.

As the ersatz Edwards figure, Richard Johnson's

rueful Conrad enjoys little of the limelight, pushed to the margins by some

imposing ancillary characters - Donna Dent's inwardly grieving nursemaid and

Rosaleen Linehan's insensitive Cassie[sic], every inch Gabriel's

sister.

Mac Liammoir once remarked: "Life is a long

rehearsal for a play that is never produced." Well, he's finally been proved

wrong - and one must embrace this moving, wistful homage for all its evident

frailties. |

|

Dominic Cavendish

Daily Telegraph, 7.5.02.

Subtle history good as gold

A work of fiction drawing on the lives of two

men whose dedication to theatre created the very stage on which it is played,

this is the subtle circle which forms Frank McGuinness' latest play, premiering

here at the Gate Theatre. MacLiammoir and Edwards are silently referenced,

their names only mentioned in the programme.

Gabriel, a great actor, is nearing the end of

his life somewhat prematurely and these final days are watched by his partner

and director Conrad. Alan Howard and Richard Johnson, English actors of

suitably distinguished backgrounds, make their Gate debuts in these lead

roles.

Gabriel is a bitter yet funny man whose life is

so intimately bound with theatre that every moment is a rehearsed drama. The

nurse Alma (Donna Dent) who comes to care for him becomes a new target for his

scathing comments as he teases out the details of her life. |

|

Visits from his sister Cassie [sic], played by the

delightful Rosaleen Linehan and his nephew Ryan (James Kennedy) provoke musings

on a life which has left him no children but the theatre he and Conrad founded

together - family redefined.

The hard lines of Joe Vanek's Japanese-themed set

offer an aesthetic contrast to the Shakespearian moments of Gabriel's

speeches.

The play is taken up almost completely with

ruminations on dying and the consequences of a godless life for one now seeking

immortality and as such becomes highly personal. It never lets you out of the

dying man's range and though at times witty, it is a relentless

exploration.

Deirdre Green

The Stage, 9.5.02.

Gates of Gold

at The Gate Theatre

A portrait of two men, young, classically beautiful,

and rendered heroically, looms equally over the stage and the story that

unfolds in Gates of Gold, Frank McGuinness' latest play, and homage to the

roots of the Northside theatre, and to the courage of two who lived openly as

lovers in an era in which homosexuality was openly not tolerated.

The picture's symbolism has the effect of needlessly

hammering home myriad metaphors, not the least of which being the lionisation

of youth in gay culture, as juxtaposed to the ageing and dying that is at the

play's centre.

Gabriel (Alan Howard) is dying, and as is expected,

is going about it rather dramatically. The 'flamboyant' half of the pair - the

stoic Conrad (Richard Johnson), is the 'masculine' half - he is nursed by the

no-nonsense Alma (Donna Dent) and chases away his fears of death and dying by

spinning outrageous tales of his youth, probing Alma's memories, and declaiming

speeches that stand as highlights of Western dramatic literature. As young men,

Gabriel and Conrad had built a theatre, a theatre of dreams, and in their old

age, bicker and banter as a way of keeping the encroaching shadows at

bay.

McGuinness' dependably lovely and colloquial dialogue

takes us through this multi-layered tale of death and dying, Heaven and Hell,

love and hate, with his usual idiomatic poetics, but the overdressed set,

designed by Joe Vanek, and Patrick Mason's utterly literal and uncomfortable

staging of the piece takes away from its ethereally concrete text. Ethereally

concrete? There's always a paradox at work with McGuinness, and the limbo

between death and dying deserved a better treatment than the Noel Cowardesque

drawing room and boudoir that it received.

Howard's rich performance of Gabriel is a

barnstormer, and only Rosaleen Linehan, playing his sister Kassie, is able to

truly hold her own in his presence. His superbly varied and modulated voice was

a symphony of tone and colouration, and he ably handled the crucial role of

anchoring what was a less than even-handed rendering of a text that is more

complicated than it may first appear.

Susan Conley

INDUBLIN, 9th-22nd May 02.

Other Comments

....what we have is a superbly drawn portait of

MacLiammoir, played as the character Gabriel on stage, and it is for him alone,

and Alan Howard's intelligent, charismatic portrait of a man at once as dark as

he is adorable and as cruel as he is gentle and kind, that this play is worth

watching.

For all the talent on stage, the assurance of

direction by Patrick Mason, and the marvellous stage by designer Joe Vanek, it

is thrown into shadow by the enormous reality of just one man.

Rachel Andrews

The Sunday Tribune, 5.5.02.

........ Gabriel is played expressively in a

tradition that comes down to us in Dublin theatre from Anew McMaster and

Micheal Mac Liammoir. The actor is Alan Howard, and the performance is well

judged, never falling into the caricature of the 'gay person of the theatre'

that one anticipates in the play's subject matter.

Bruce Arnold

Irish Independent, 2.5.02.

..... Howard taps into the great strengths of

McGuinness's writing: the courage to leap into the emotional dark of real lives

and to imagine a gay relationship without sentimentality.

Fintan O'Toole

Irish Times, 2.5.02

.... Alan Howard as the fading grandee has not been

so original or remarkable in many moons.........

Michael Coveney

Daily Mail, 3.5.02.