|

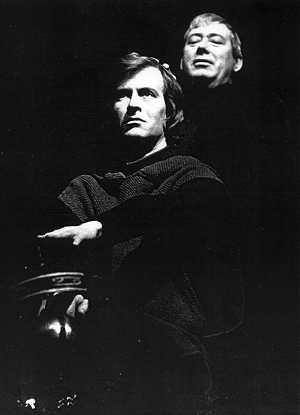

Next Thursday sees the opening night of the Royal Shakespeare Company's new "Hamlet", with Alan Howard as the prince. In 1965 this part with this company brought fame to David Warner. SALLY BEAUMAN asks if the same will happen to Alan Howard, another RSC actor whose work has already stirred the critics "My dear! Has no one ever told you you're the image of Gwen ffrangcon-Davies when young?" The woman who says this has one of those deep brown husky voices peculiar to all actresses over the age of 40, who have had their voice boxes toughened and tanned by years of projecting to the back row of the upper circle. Just to get it really ripened up, she is also chain smoking. We are in the Green Room at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-on-Avon, which - as someone points out - is neither green, nor much of a Green Room in the way anyone who watches bad theatre movies imagines: i.e. a chic little room where Temperaments sit round playing poker before they go up onstage. This room is small and grubby in the manner of one of British Rail's less-inspired station buffets, with tea and coffee in urns, and a few current buns on doilies wilting in a small glass case. The room is full of people and smoke but through the smoke some of the people are recognisable if you concentrate: Norman Rodway, who plays Richard III this season, is there: and Helen Mirren, who plays Ophelia: Brenda Bruce and Sheila Burrell line up for coffee, clutching their long black rehearsal skirts around them. It is very noisy, in the way that rooms full of deep brown voices used to projecting inevitably are. In the midst of the mêlée sits Alan Howard, whom I have come to see. He is over in the corner looking sort of pale and hunched up and - perhaps appropriately for someone who is playing Hamlet this season - contemplative. At any second he and I and some other members of the cast are going to clamber into what he promises me is a cold and draughty minibus and commute to Oxford, where he is acting in a pre-Stratford run of Dr Faustus, playing the devil, Mephistophilis. Norman Rodway and Helen Mirren are also going, though only to watch, and they offer us a lift in his lovely warm fast car. "No," says Alan Howard firmly, "she's going to see what it's really like." So we get in the minibus, and it is as he said. Very cold. Very draughty. For Alan Howard this is the beginning of a new and testing season, which culminates in the opening performance of Hamlet on June 4. That date is now some two months away: he has not started rehearsals yet: he does not like to think about it all too much. He says he deliberately never read the play till now, because, in a superstitious way, he was waiting. He has seen it performed only three times, which for an actor is quite a remarkable achievement. Now he carries a paperback edition of the play everywhere he goes, but if you ask him about it he wails in mock terror, "Don't let's talk about it. It scares me witless." It is all the more difficult for him, of course, playing Hamlet at Stratford, because of the obvious parallels between him and the last Royal Shakespeare Company Hamlet, David Warner, who played the part in Peter Hall's celebrated production in 1965. Before he played Hamlet, Warner - although he came up much faster - was at exactly the same stage of semi-celebrity that Alan Howard has reached now. Howard is well known to people within the theatre (where reputations begin) and to people who go to the theatre often. Outside of that he is not well known, as indeed, few actors are, unless they are very grand like Scofield or Olivier, or unless they go into films. Before David Warner played Hamlet he had attracted the attention of audiences and critics with other performances at Stratford, particularly with his playing of Henry VI in The Wars of the Roses. After playing Hamlet he not only went on to some marvellous parts in the theatre, but started turning up in innumerable movies. Hamlet, which still is, for better or worse, regarded as some kind of test part, enabled him to make that leap. There have been signs for some time that Alan Howard might be the next RSC actor to follow him: last year Howard received the Plays and Players London theatre critics' award for the Most Promising New Actor. He had four leading parts in the last, highly praised season at the Aldwych - namely, Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, Bartholomew Cokes in Bartholomew Fair, the evil Lussurioso in The Revenger's Tragedy, and his Achilles in John Barton's unforgettable production of Troilus and Cressida. And the way he played those roles stirred it up a good deal with the critics, which is never a bad thing. In the back of that cold minibus he tells a long, complicated and funny story about how how he was once arrested for supposed drunken driving in Los Angeles, and had to pass a series of sobriety tests for the cop who arrested him. He had to walk several straight lines. He had to lean over backwards and close his eyes; then, with his eyes still shut, and arms outstretched, he had to bring in one hand in a steady arc, and touch the tip of his nose precisely. Goodness knows how difficult this is to do if you have had anything to drink. Alan Howard demonstrates it in the back of the bus, and even without the hindrance of alcohol it looks pretty impressive. We get to the theatre and I sit guiltily in his dressing room while he puts on his make-up for Mephistophilis, feeling somehow that my presence must be coming between him and his muse, or whatever it is actors are supposed to commune with before they go onstage. Anyone would think that he was just getting washed before going off to the office or something, and I find this sangfroid: I mean, is he always like this? Surely he won't be before Hamlet? |

|

He takes off his spectacles for the first time since we have met, and it is astonishing how different he looks without them. He is very short sighted and therefore peers at the mascara and pancake, holding it approximately one inch from his eyeballs, putting it on very quickly and without embarrassment. Without his glasses, you can see the resemblance to the rest of his theatrical family, though he does not like this emphasised. His family have been in the theatre for five generations. His great great grandfather left Scotland and changed his name from Mackenzie to become the actor, Henry Compton: he once played the grave digger to Henry Irving's Hamlet. His great grandfather, Edward Compton, was an actor manager. His great aunt is Fay Compton; his mother, Jean Compton, also an actress, died some years ago. His father is Arthur Howard, perhaps best known for his part as Mr Pettigrew, Jimmy Edward's terrified sidekick, in the TV series, Whacko! From the age of six Alan Howard was at boarding school, and, since his parents were both working, spent most of his holidays with his great uncle, who had a house in the Hebrides. The great uncle is Compton Mackenzie. But perhaps the person Alan Howard most resembles, out of this daunting number of theatrical and literary relations, is another uncle, the late Leslie Howard, Hollywood's ultimate Englishman in innumerable movies, and Ashley in Gone With the Wind. |

|

|

He has the same pallor, and the same, almost equine, narrow features. But, unlike his uncle, who always looked so delicate and fragile, Alan Howard onstage has a strong physical presence, and his face is a stage actor's face, infinitely changeable, malleable. As Achilles in Troilus and Cressida it seemed to narrow until it assumed the measured profile of a Greek classical head on a vase; as the childish Bartholomew Cokes in Bartholomew Fair, his face seemed to broaden, suddenly he looked lumpen, ungainly, with uncontrollable feet and hands, rustic reddened features. All Alan Howard's work has been remarkable for what has been called, variously, a controlled eccentricity and startling originality. When he played Jacques, in 1967, some of the critics were disgruntled by its fierce melancholia, and by the speaking of the "All the world's a stage" speech as an intensely bitter commentary on the futility of the human condition. Alan Brien wrote: "Alan Howard as Jacques, the most grinning melancholic on record......seems to be reading into his lines some cryptic interpretation of his own." It is a charge which has been repeated about almost all his roles: his playing of Benedict as gauche rather than smooth and slick seemed to some critics to be nothing short of heresy. His Achilles, played in a long white silk dressing gown, his blond hair plaited into a bun at the nape of the neck, aroused fury in audiences and critics. "Is there any justification in Shakespeare's text," W. A. Darlington wrote, "for turning Achilles into not merely a homosexual, but into an effeminate transvestite type of homosexual, as soft as a feather bed?" "To suggest that Achilles is a homosexual is just not on," a Stratford colonel wrote in protest. Alan Howard, rightly, has confidence in what he is doing, and shrugs off such criticism. "I played Achilles in a dressing gown," he says, "because I haven't the biceps to play him any other way. I told John Barton I could strip fairly well, but I couldn't manage that much. And as for the hair, well, have some of these people never looked at a Greek vase?" Other critics vindicated his decisions: "His Achilles," wrote John Barber, "gives the near-tragic impression of a self-tortured egotist at bay." "Alan Howard's Achilles," wrote Harold Hobson, "seems to me to be of a higher order of excellence now [i.e. at the Aldwych] than it was at Stratford; or perhaps my eyes are opened. Mr Howard accepts all the difficult aspects of Achilles' character.........in the scene in which Hector is murdered, Mr Howard's Achilles is at least as grand as he is hateful. Cool, graceful and terrifying, his body painted with black snake-like curves, he towers balefully like something magnificent and evil from primaeval Africa. The effect is tremendous." When Faustus ends we climb into the bus for the return journey to Stratford. It is about an hour's drive. The play would run in Oxford for one week, then one week in Cambridge, and then finally open in Stratford, when Howard would begin rehearsing Hamlet in earnest. As soon as Hamlet opens, after only six weeks rehearsal, he is due to start work on his next part, that of Theseus in Peter Brook's production of A Midsummer Night's Dream. It is even colder on the bus for the drive back, so everyone covers up their knees with some old costumes which are lying on the floor in the back. I turn out to have the black leather crotch piece of Ian Richardson's armour for Coriolanus. Which is a nice way to keep warm. Alan Howard is 32, and, in many ways, a perfect example of the workings of the English theatre system; certainly he is much more typical than actors like, say, Scofield or David Warner, who were recognised fairly early in their careers, and rarely had to look for work. Outsiders often do not realise how high the odds against such success are in the theatre. Equity at present estimates that out of the 14,000 cardholding actors and actresses in this country, 10,000 are unemployed, and that many of the remaining 4,000 only manage to make up the minimum wage of £12.00 a week by doubling and trebling up on understudy parts. The position of an actor like Howard, one of only 39 Associate Actors under long-term contract to the RSC, is exceptionally rare, and much fought for. |

|

Alan Howard is married now, to RSC designer Stephanie Howard, whom he met in Nottingham. Because of the difficulty of acting one year in Stratford and one in London at the Aldwych, they have been forced in the past to keep a flat in London and to take rooms in Stratford. They still have a small flat in Kilburn, "which is," he says, "terribly cramped. I have to learn my words in the same room that Stephanie is experimenting in with costumes. Not the perfect situation." |

|

|

Now, however, he is buying a house, a small one with a bright blue front door not far from the Stratford theatre. They will have moved into it by the time he plays Hamlet. The house itself is a mark of a new kind of stability in his life, a stability which was always impossible before. In the past his life was the typical one of the good, moderately successful actor: he lived where there was work and his work alternated between really good parts with enthusiastic reviews, and unemployment. He never trained formally for the stage, but went straight to the Belgrade theatre, Coventry, where he pushed a broom about as an assistant stage manager until he was finally offered a part. He created the role of Frankie Bryant in Arnold Wesker's Rootsand then played in each play in the Wesker trilogy when John Dexter directed it at the Royal Court. He played Alonzo in Tony Richardson's production of The Changeling, with Mary Ure and Robert Shaw. He was out of work. He played the lead in William Inge's The Loss of Roses, at the Pembroke, Croydon. The production was praised, but never made it to London. He was out of work again. He acted in Laurence Olivier's first season at Chichester, with good parts in two of the plays, The Chances and The Broken Heart; it was the third play, however, Uncle Vanya, which attracted all the praise and attention, and which went on to form part of the repertory at the new National Theatre. He made a film, The Heroes of Telemark, about a group of men who blew up a German heavy water station in Norway during the war, just as the Germans were about to discover nuclear power. He was promised great things by the producers. "There were supposed to be nine of us, Kirk Douglas and Richard Harris and seven others. In the end we called ourselves the Insignificant Seven. It took four months and I appear occasionally in the corner of a frame if you look carefully." Back in England again, he had the leading role in the stage version of Ivy Compton Burnett's A Heritage and its History. It ran for several months in the West End, and after that he was invited to act at the Nottingham Playhouse, where he had two great opportunities, Angelo in Measure for Measure ("I played him as a sort of young Mao Tse Tung figure") and Bolingbroke, one of the performances he is most proud of. He was then out of work again, for four months. Then, suddenly, he was asked to appear in a production of Twelfth Night for the RSC. Later that year he played Burgundy in Henry V: then Lussurioso. At the end of 1966 he was asked to become an Associate Artist with the company. Statistically the odds against him were very high, but he had made it. As a person he seems nervous, abrupt, edgy and exceptionally honest, sitting back and observing people, and then suddenly entering the fray with violently expressed approval or disapprobation. He is funny, quick to pick up the phoney, and good at putting down people, including himself. Yet there is something elusive and unresolved about his personality, a complexity which he perhaps uses in his acting. "The idea of a smooth consistent character," he says, "is rubbish. Stage characters should be allowed to be as varied and inconsistent as people are in life." And it is clear that he draws introspectively upon himself for most of his parts. "I think," he says, "that acting is a bit like grafting. You find some part of yourself that is applicable, relevant to the role you're playing, and you separate it, graft it on to the character you're playing. And then the other things in the play, the other characters, their lines, work on it. Then, if the graft is right, it begins to grow of its own accord. A part of yourself you normally try to suppress you encourage to flourish onstage: it can be quite alarming. And if it's working right you can do things, with your body, with your voice, that you wouldn't be able to do off stage, outside of the part." Perhaps because he does draw so much upon himself for his acting, the experience of playing several roles in repertory, as he did last season, can be an almost schizoid one for him: "You're operating on three, four, five decks at once; there are five different extensions of yourself happening simultaneously, and in the middle of all that, somewhere there is supposed to be you. Mister Me. But sometimes when I look back on those times, I look, and I don't see me at all." It is an experience which has obvious parallels in Hamlet but he does not say so, still shying away from discussion of the play. Although he is not going to begin rehearsals until he returns to Stratford, he and Trevor Nunn intend to meet in Cambridge during the run of Faustus and talk about it. "In fact," says Alan Howard, smiling, "what we'll probably do is walk all round Cambridge and Trevor will tell me all the things he used to do when he was up there, and we'll never mention Hamlet at all...." I ask what would happen if he and Trevor Nunn turned out to have diametrically opposed conceptions of the part. Alan Howard tries to look grim, which he is not very good at, offstage. "See my fingers, see my thumbs," he chants. "Watch my fist, here it comes." He is joking; but his answer reflects the basic independence that marks him as an actor. So - whatever happens on Thursday, and it's bound to be exciting - Trevor Nunn, critics, letter-writing Stratford colonels, audiences: don't say you weren't warned. Sally Beauman The Daily Telegraph Supplement, 29.5.70. |